Once upon a time, Asian-American artists would have taken their anger to the streets.

That's what happened in 1990, when Asian-American actors, outraged over a Caucasian actor's yellowface performance in Miss Saigon, staged public protests over the casting choice. It was one of the most divisive debates over racial representation in the history of the American theater. Twenty-two years later, the battle is still being waged — though now it's via social media and a PowerPoint presentation.

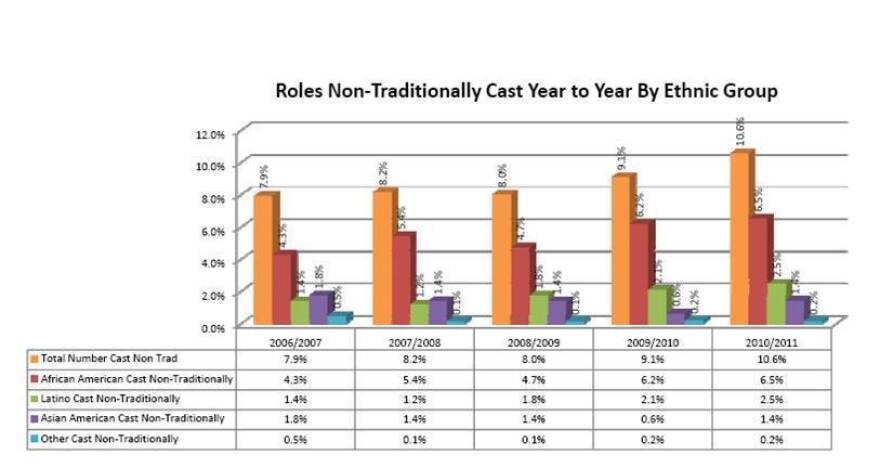

At the RepresentAsian conference, a three-hour wrangle at Fordham University on Monday, it wasn't about slogans, signs or sit-ins. Cold numbers, pie charts and bar graphs told what Asian-American advocates say is a sad fact about casting. Based on data the group compiled from the past five theater seasons, Asian-Americans are the only minority group whose share of New York acting roles declined, and they were also the least likely to be selected for roles that would traditionally be played by white actors.

More than 400 people — nearly three-fourths of them performers — converged for a roundtable with 17 theater-makers: Broadway director Bartlett Sher, Vineyard Theatre head honcho Doug Aibel, playwright Douglas Carter Beane, plus producers Nelle Nugent and Stephen Byrd, Actors' Equity boss Mary McColl and more.

The moderator? David Henry Hwang, the same Tony Award-winning playwright (Chinglish, M. Butterfly) who emerged as a spokesman when the Miss Saigon clash erupted.

Calling themselves the Asian American Performers Action Coalition, the assembled advocates were variously upset, fed-up, frustrated, irritated, indignant and disillusioned at what they say is a lack of true diversity on stage — and specifically a lack of Asian-American representation.

And the numbers? With 6,639 total roles cast in the past five theater seasons, 54 Broadway parts went to Asian-American actors. Another 100 Asian-American actors landed gigs at nonprofit companies.

Where roles were not racially specific — think Shakespeare and other period plays, chorus or ensemble members in a musical, or just stories where race isn't overtly addressed — African-American actors were more frequently cast than other performers of color.

"African-Americans were cast in 13 percent of all available roles, Latinos in 4 percent and Asian-Americans in 2 percent," the report states.

That's despite the fact that Asian-Americans make up 12.9 percent of the population of New York City — and are considered the city's fastest growing minority group. (Latino performers, who've considered the issue from their own demographic angle, have voiced their own frustrations over what they've called a "brownout.")

Beane, who wrote the books to the two Broadway musicals with the most diverse casts this season — Sister Act the Musical and Lysistrata Jones -- said the numbers are shocking.

"The stats baffle me," he says. "Casting directors of every show I've worked on have always asked at some point, 'Can we open this up? Can this character be black, Latin or Asian?' ... You want the stage to look like the street, not some fantasy world that doesn't exist."

'Taking The Emotion Out Of The Equation'

After AAPAC began to coalesce — initially through conversations on Facebook — it became clear that organizers wanted to reshape the status quo without rocking the boat too hard. The question, says actor Christine Toy Johnson, became, "How do we engage in dialogues with the New York theater community without placing blame?"

"It was important to take the emotion out of the equation," adds actor Pun Bandhu, who's currently on Broadway in the Manhattan Theatre Club revival of Wit. "This movement isn't just about advocating diversity. Who could possibly be against that? Our movement is about Asian issues. It's important that this movement have an Asian face, because Asians have remained silent for too long. "

The report assigns grades to Broadway shows, as well as to 16 nonprofit theater companies, on the basis of how frequently they have cast nontraditionally — meaning choosing women or ethnic minorities for roles where race, sex or ethnicity are not germane.

One problem, the actors argue, centers on how nontraditional casting has been defined and employed in New York theaters.

"Whether or not there are new plays with roles for Asians, this should not deter Asians from working in the theater," Bandhu says. "There are Asians who are older, who are younger, who are fat, who are skinny, who are leading men, who are character actors. Yet we are all vying for the same role — just because that role is written as an Asian role."

Adds actor Anitha Gandhi: "When contemporary plays are produced, we're not looked upon for roles of the girlfriend, best friend, mom or father. I feel the color angle really does us a disservice. There is this patting-the-back mentality among producers and casting persons who will say, 'There is a black actor in my production.' ... They don't look at us as being part of the fabric of the American story."

Again and again, speakers at the Fordham gathering agreed that part of the issue is "a crisis of imagination" — and a fear among playwrights and directors that if too many people of color are cast in the same show, a production might be seen as somehow "conceptual."

"When money is on the line," says actor Peter Kim, "people tend to go with the safest choice. Usually that results in casting 'names' of some sort, whether it is a television, film or theater 'name.' Since there aren't many Asian-American 'names,' they aren't being considered for roles."

Moderator Hwang scored points with the crowd with one particularly timely analogy. Describing "the insidiousness and banality of the glass ceiling" for actors, he invoked the name of Jeremy Lin, the Chinese-American who overcame a lack of interest among basketball recruiters to become a breakout sensation as a guard for the New York Knicks.

"Institutions were making assumptions about Lin," Hwang says. "When you have a glass ceiling, it hurts not only the people being discriminated against. It hurts the institutions doing the discriminating."

'The Servant Of Many Masters'

Scoring lowest on the report's grade scale was Off-Broadway's Atlantic Theater Company, founded by writer David Mamet and actor William H. Macy in a Chelsea church more than a quarter-century ago. Its current chief, Neil Pepe, seems to echo Kim's analysis, at least indirectly.

"As artistic director of an ensemble-based theater, I find that I am the servant of many masters in programming and in staffing our seasons with artists," says Pepe, who couldn't attend the RepresentAsian roundtable. "The statistical results of the survey are a welcome reminder to us that there are many groups of artists in New York who are underrepresented on our stages."

Still, Pepe continued, "we are happy to report that 33 percent of the actors in our current season are non-white, and that none of our six productions had or will have an all-Caucasian cast. ... We certainly believe that racial and ethnic diversity among our artists only [adds] depth and complexity to the work."

Oskar Eustis, the famed artistic director of the Public Theater — another institution once targeted publicly for hiring white actors to play Asian characters — did attend the roundtable. He acknowledged the collective diagnosis as "both true and regrettable," and promised that an evening spent "with people who are thinking about this issue seriously, and who are impacted by this problem," would force him to "make it a higher priority. That is what pressure is supposed to do to institutions."

That might be of some comfort to actor Julienne Hanzelka Kim.

"Personally I'd rather be in an empty room, looking at a script and trying to figure out the psyche of a given character, than culling statistics on diversity and trying to get industry leaders to pay attention," she says. "But this is perhaps what we need to do in order to get into that rehearsal room much more often."

Randy Gener is a New York-based writer and editor, and the 2007-2008 winner of the George Jean Nathan Award for drama criticism.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDM3NjYwMjA5MDE1MjA1MzQ1NDk1N2ZmZQ004))