If you had to leave the country where you were born and raised, what would you bring with you as you begin a new life in a strange place?

Of course, there are necessities to pack. But perhaps there is something that is not essential and yet in a way is just that — something to help you remember your roots and keep a touch of home in your new dwelling place. It could be a physical object — or perhaps something intangible that you carry in your heart and soul.

At this time of unprecedented numbers of refugees — a record 27.1 million in 2021 — we wanted to know what precious possessions did refugees take with them? The photojournalists of The Everyday Projects interviewed and photographed eight refugees from different parts of the globe. Here are their stories — and the stories of their cherished objects.

Note: In the story about the Afghan refugee, the photojournalist herself is the one who fled.

From Ukraine to the U.S.

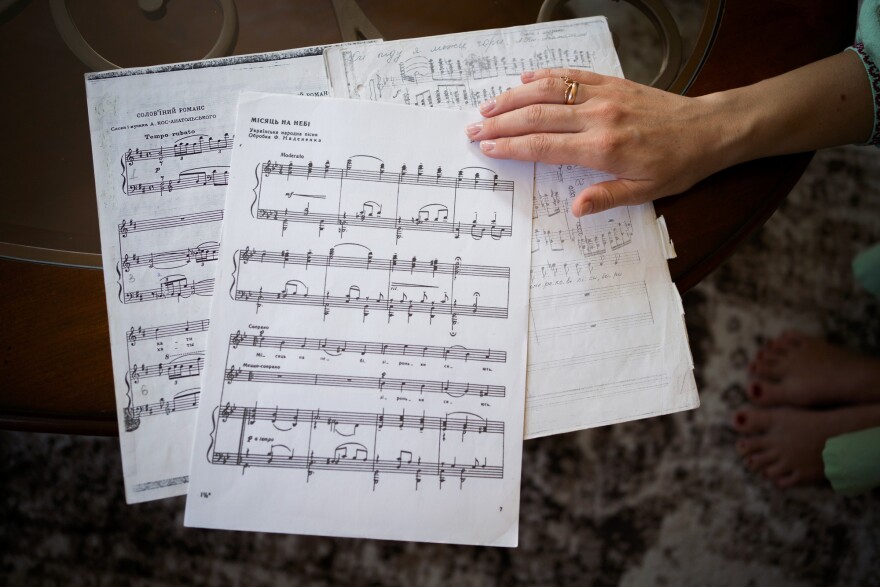

An opera singer's beloved Ukrainian sheet music

Earlier this year in Khmelnytskyi, western Ukraine, Olha Abakumova, an opera singer, and her husband, Ihor, a tubist, put their then-7-year-old daughter Zlata on a pile of blankets in the bathtub to sleep. If a missile were to strike, the bathroom seemed like the safest place in their ninth-floor apartment.

The Khmelnytskyi Philharmonic Orchestra, where they both worked, initially closed after Russia's invasion. A month later, it reopened and the orchestra kept having concerts, raising money for the war effort.

Olha and Ihor were determined to remain in Ukraine even while many of their neighbors fled. They believed the war would end quickly. But one starry and particularly quiet night in March, they heard an eerie whistling sound. They soon learned that Russia had attacked the nearby city of Lviv, where Olha had made her debut at the Lviv National Opera almost a decade ago. That was when they decided to leave.

Today, Olha and her daughter are living in a leafy suburb of Boston with Olha's sister, Liliia Kachura, and her family. Liliia moved to the U.S. eight years ago and now lives in Sudbury, Mass., with her Ukrainian-born husband, Sasha Verbitsky, and their two young sons.

In late April, President Biden announced the Uniting for Ukraine program, which allows U.S. citizens to sponsor Ukrainians to come to the U.S. When Verbitsky heard about it, he immediately called Olha, encouraging her to apply. Men of military age still have to remain in the country, so Ihor would stay in Ukraine. Within a few weeks, Olha's application was approved. In May, mother and daughter were on a 14-hour bus journey from Khmelnytskyi to Warsaw.

Olha and Zlata carried one small suitcase. In it they put toiletries, clothes and shoes. They also carried a few items with sentimental value: Olha's mother's 50-year-old Vyshyvanka, a traditional Ukrainian embroidered shirt; Zlata's favorite stuffed animal, a turtle; and — most important for Olha — as much sheet music as Olha could stuff inside.

"I have a lot of different Ukrainian and Russian music, but when I fled, I took only the Ukrainian arias," says Olha. "The Ukrainian works are very important to me. They connect me with my motherland, culture and my roots."

When mother and daughter arrived at Logan airport in Boston, Verbitsky was there to greet them and take them home. Soon after, Olha found a free piano advertised on Facebook. Verbitsky and Kachura arranged to get the piano for Olha's birthday. It's now in the children's playroom, where she practices and sings with her sheet music from Ukraine.

"When I'm singing, I see pictures in front of my eyes," Olha says. "The words and music move through me and take me back to Ukraine."

Some lines, like the last ones in the song "My Ukraine," bring her to tears.

You walked through thorns to reach the dreamed-about stars.

You planted goodness in souls, like grains in the soil.

This past August, hundreds of Ukrainians gathered in a churchyard in Boston to celebrate their Independence Day. Olha came dressed in a mint-colored Vyshyvanka. When she sang the Ukrainian national anthem, people stopped what they were doing and stood at attention.

Her melodic voice carried across the churchyard, past a jungle gym full of playing children, through the tents where vendors were selling Ukrainian souvenirs and T-shirts. People who had been heaping their plates with homemade cabbage rolls, pierogis and sausages paused to listen.

In August, Zlata celebrated her birthday in the U.S. with her mother, aunt, uncle and cousins. But her father, Ihor, could only congratulate his daughter over video chat from Khmelnytskyi.

Olha worries about her family still in Ukraine, some of them fighting on the front lines, and dreams of a reunion.

"I hope the war will end soon," she says. "I believe it will, but at what cost?"

— Photographs and interview by Jodi Hilton

From Afghanistan to the Netherlands

A traditional dress that was a mother's gift

On Aug. 25, 2021, exactly 10 days after the fall of Kabul to the Taliban, I left Afghanistan with my husband.

It was between 10 and 11 p.m. when we got a call that we had to go to Kabul airport immediately. We left the house in darkness without saying goodbye to the rest of our family. We didn't have enough time. There were several Taliban checkpoints we had to pass through to get to the airport.

My husband had worked with the government and international organizations, and I had worked with international news agencies. The Taliban often kill those who work with foreigners — we felt our deaths were certain if we stayed in Kabul.

The weather was hot, and the city was dark. The only working lights were around the airport. As we got close, I remembered a Hollywood movie where zombies attack a city and the people flee, trying to save their lives. It felt like all the people of Afghanistan had come to the airport to escape.

As we stood outside the gates of the airport, trying to get in, the Taliban were all around us, shooting in the air. A Taliban soldier hit my husband on the shoulder with the butt of a Kalashnikov. I was next to him when it happened, holding his hand. We quickly ran to the other side of the street. My husband didn't bleed, but he couldn't lift anything for the next six months. About seven hours after the Taliban hit my husband, we were finally able to enter the airport.

All I had with me was one backpack to contain my whole life in Afghanistan. The airline allowed only one bag on the plane, and I brought as small a bag as I could. I knew that in the crowded airport, surrounded by thousands of people like me, it wouldn't be possible to carry anything heavy.

Two days before we left, I packed. I took all of my clothes out of the closet and threw them on the floor to better see them along with my other possessions.

I never thought I'd leave them like this, losing the precious things of my life: My photography books, which I had found across Kabul and Iran. The first gift from my love — a red bear from our first Valentine's Day. I had wanted to keep it for as long as I lived. The notebook in which I had written 15 years of my memories. My childhood photo album.

Most of the things I could not take I gave to my relatives to give to the poor. Other things I burned, like my photo album, so they wouldn't fall into the hands of the Taliban.

With just a few pieces of clothing in my backpack there was no more empty space. I had to close the zipper, but suddenly I saw the green dress with small pink and red flowers that my mother had given me after my wedding.

It's a dress that belongs to the Hazara people of Afghanistan, my parents' ethnic group. I stared at it for a few minutes and without thinking I put it in my backpack. With a lot of pressure and my husband's help, we closed the bag.

I understand today that I couldn't leave the dress and the memory of my mother. I didn't know if I would see her again. I couldn't leave this symbol of my ancestors that never lets me forget where I belong.

I've now been in my new home in the Netherlands for a year. Every time I open my wardrobe and see the dress, memories of the past come to my mind. But I haven't worn it — yet. I plan to wear the dress for the first time outside Afghanistan at the opening of my photography exhibit in Amsterdam next month.

— Photographs and text by Nilofar Niekpor Zamani

From Honduras to the U.S.

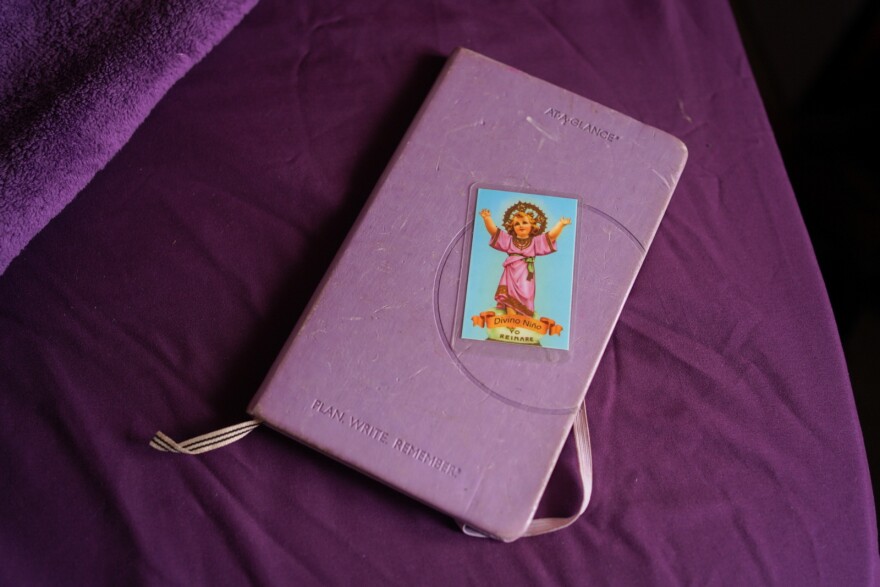

A purple diary that's a symbol — and a record — of a transgender woman's journey

While grilling meat for lunch with friends on a quiet afternoon, Kataleya Nativi Baca received the phone call she'd been hoping to get for more than a year.

It was April 2021, in Tijuana, Mexico, nearly two years since the 31-year-old left Honduras after she says a family member beat her up, fracturing her collarbone.

"In my country there's no future for [LGBTQ+] people," says Baca, who is a transgender woman. "The only future we have is death."

When she fled her home "like a fugitive in the night," Baca headed toward the U.S., where she hoped to seek safety. In San Pedro Sula, Honduras, she had suffered discrimination, threats and abuse from family, neighbors and gang members since childhood.

Baca hoped that things would be different in her new home. "Maybe on the other side, I can have the life I've never had in my country," she says.

As for Baca's travels, she says she "wouldn't wish it on anyone." She crossed the Suchiate River between Mexico and Guatemala and then remained in Tapachula on the southern border for a few months. When she first arrived, she had no money and slept on the streets. She finally made it to Tijuana in September 2019.

When she first got to Tijuana she received a number that would give her a sense of when she might be able to officially apply for asylum and hopefully enter the United States. She thought her number would be called around March 2020. But the borders closed indefinitely due to COVID-19 and she was stuck in Mexico without any idea of when she might be able to enter the U.S.

Baca lived in multiple shelters. In one, she initially was friendly with the coordinator, but once she got a boyfriend "everything changed" she says, and the coordinator wanted her to move out. On one occasion, the coordinator "started to yell as if a demon was inside him," she says. He ultimately hit her. Finally, she moved in with her boyfriend, but one of their new landlords was transphobic and threatened her. In fear for Baca's safety, her lawyer filed a humanitarian parole request to speed up the process of getting her across the border.

On that afternoon in Tijuana, the moment had finally come. "You're going to enter the United States. Congratulations," said her lawyer's secretary on the phone. Crying, Baca shared the news with her friends.

Two days later, on April 8, 2021, she walked through the San Ysidro Port of Entry between Tijuana and San Diego in the same jeans she wore when leaving Honduras. Advised to bring one small suitcase, the only thing Baca could think of to pack besides a few pairs of clothes was a prayer card — and her diary. Of all her possessions, the diary is most important.

Given to her by a coordinator of an LGBTQ+ shelter where Baca briefly stayed in Mexico, the diary has a purple cover. It's her favorite color.

"I've written most of what I've lived through along my journey up through arriving here in the U.S.," said Baca, who now lives in Virginia.

It also includes directions for arriving in America, a letter to her mom about living "a few steps away from the U.S." in Tijuana, and lyrics to a song by Mexican singer-songwriter Marcela Gándara, beginning with "It was a long journey, but I've finally arrived."

The diary is both a symbol — and a record — of her journey, she says: "I've written most of what I've lived through along my journey up through arriving here in the U.S."

Baca's life in Virginia has not been easy. A transphobic landlord evicted her and she has struggled with her expenses. She tries to remain hopeful as she continues the asylum-seeking process. "I want a dignified home, a family, and to succeed on my own," she says. "I just want to be happy. That's the only thing I want."

— Photographs and story by Danielle Villasana

From Liberia to Nigeria

A passport that's 4 decades old

!["This passport reminds me of my past life, traveling across West Africa. There was a time I wanted to throw the passport away, but [my pastor] said I should continue keeping it," says Rebecca Maneh Nagbe, known as Mama Sckadee. After fleeing the civil war in Liberia in 2003, she came to a refugee camp in Nigeria. She has not been able to obtain legal status that would let her to leave the camp.](https://assets.vpm.org/dims4/default/bdeb1e5/2147483647/strip/true/crop/3000x1998+0+0/resize/880x586!/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.npr.org%2Fassets%2Fimg%2F2022%2F10%2F19%2F2022-npr-edp-refugees-obasola_02_custom-d4095a899743dc410b3428c96eaabd46262d9ff7.jpg)

Rebecca Maneh Nagbe, popularly called Mama Sckadee, is a 69-year-old Liberian refugee living with her 14-year-old granddaughter, Angel, at the Oru-Ijebu refugee camp in southwestern Nigeria. Nagbe left Liberia in 2003 during its second civil war.

"I was working at the Liberia International Airport and living close to the airport in Monrovia," she says. "The effect of the airstrike was too much for me to bear. It was then I made up my mind to find an escape route through my church."

Nagbe went to her church to find shelter with other congregants. When the Nigerian government provided a plane to evacuate Liberians from Monrovia, Nagbe took her 11-year-old daughter, Ajua, on the flight to Nigeria.

When Nagbe first arrived in Nigeria, she was legally considered a refugee. But for the past decade she's been in political limbo. Because Liberia has restored peace, in June 2012 the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees stopped regarding Liberians as refugees. Many host governments, including Nigeria, stopped granting Liberians like Nagbe a special legal status. She applied to Nigeria's refugee organization for an exemption, but her request was rejected.

That's why Nagbe still clings to her old Liberian passport from 1982. She got it at the old immigration office in Monrovia and she's kept it close for four decades.

"I will always keep this passport because it reminds me of so many things, one of which is the United States visa I have on it," she says. "My Sierra Leonean boyfriend wanted me to follow him to the United States, that was why he got me the visa. Unfortunately, I could not join him on the trip."

"This passport reminds me of my past life, traveling across West Africa. There was a time I wanted to throw the passport away, but [my pastor] said I should continue keeping it."

While Nagbe liked her old job working at the airport in Liberia, she doesn't want to return. "I do not think I might ever return because the last time I heard about my siblings, one of them sold off almost all of our father's rubber plantation."

Nagbe had six children. One of them moved to the United States before the second civil war and she never heard from him again. "I was only able to escape to Nigeria with my youngest daughter, Ajua. So, what am I going back to? Maybe, if possible, I might visit one day, but to live in Liberia? No."

In 2008, Nagbe's daughter Ajua, then 16 years old, gave birth to Angel. When Angel was 2 weeks old, Ajua left the baby with Nagbe and traveled to Ghana in search of a better life. Nagbe says she has not seen or heard from Ajua for more than a decade.

"It was tough for me taking care of a suckling," Nagbe says. "A fellow refugee, [a] nursing mother in the camp, assisted in caring for Angel as a baby. Angel has been my companion for 14 years and people have shown us mercy along the journey of raising her. She is all I have."

— Photography and interview by Ọbáṣọlá Bámigbólá

From a rural village to India's "Millennium City"

A climate refugee brings a plate and a bowl for special meals — and offerings to God

Late one afternoon after finishing her household chores, Pramila Giri lay down on her bed to rest next to her 4-year-old son. Without electricity, the heat and humidity kept her awake. It had been raining continuously for days because of a cyclone in her village of Pathar Pratima, an island full of mangroves in the Sundarban region in India's northeast. She used a handmade fan to try to keep her son cool.

As she was about to fall asleep, she heard a cracking sound from the ceiling. In an instant she impulsively grabbed her son, then ran outside for safety. The entire roof of her house had just collapsed. Pramila and her son escaped without any injuries.

This incident in 2011 shocked the family. And the devastating cyclone was not a rare event. Scientists have found that cyclones hitting India are more intense because of climate change.

Pramila, 33, and her husband, Sukhdeb, 42, who wasn't home at the time, decided to migrate north to Gurgaon, also called India's "Millennium City." The rapidly growing metropolis bordering the capital of Delhi has multiple high-rise housing complexes, huge malls and office complexes.

"When we migrated to Gurgaon we had no jobs, no source of income and no shelter," says Pramila. "The cyclones, rising sea level and salinization of soil had wreaked havoc in our lives. Earlier we used to have three paddy harvestings in a year that took care of our needs. We were never rich, but neither were we struggling to survive. Now there is only a single harvest in a year."

Today Pramila is no longer a farmer. She works as a cook at various houses in one of Gurgaon's apartment complexes. She starts at 6 in the morning when she prepares breakfast for a family before they leave for school and work. She gets a few hours' break in the afternoon, then works in another five apartments and finishes her day at 8 in the evening. She earns about $300 per month.

Her husband works as a plumber in the same apartment complex. He earns about $200 a month. A chunk of their income goes toward rent for their crowded one bedroom in Gurgaon. But they send most of the remaining money back home to their village. They're rebuilding their house and paying for their son's education.

Supriyo, now 15 years old, lives with his grandmother in the village. His parents stay in touch through phone and video chats. His mom has plans to bring him to Gurgaon in a few years for college, but they couldn't have him live with them initially because they couldn't afford day care.

Pramila's 3-year-old daughter, Shilpa, was born in Gurgaon and lives with them. When Pramila and her husband are at work, her next-door neighbors — also a migrant family and from the same region — look after her daughter for free. "I am very lucky to have the support of my neighbor," Pramila says. "They are like my extended family. It is because of them [that] I am able to work and be out of the house for such long hours."

Other than a photograph of her son, the only other objects Pramila carried with her from back home are a plate and bowl made of bronze, locally called kansa. She uses the plate and bowl only on special occasions and festivals for offerings to God. Usually they put rice pudding in the bowl, and for the plate they put some khichdi, a salty lentil porridge.

"To be very honest I don't miss my life from back in the village," she says. "Even though we now live in a cramped one-room house, we still have relative peace of mind."

"I used to dread thinking about the floods, storms and living without the bare necessities such as drinking water and electricity for days [on] end," she says. "I have freedom here. I am able to earn and not be dependent on anyone."

Pramila says her daughter is too young to understand "the realities of our hardships," but she hopes to take the 3-year-old home to visit next year so she can see the life they left behind.

— Photographs and interview by Smita Sharma

From Tibet to Kashmir

The taste of momos: steamed or fried dough stuffed with minced meat or vegetables

A young Kashmiri man enters the restaurant shouting, "Kareema!" It's a pet name used by some of the young customers for their beloved restaurant owner, Abdul Kareem Bhat.

Bhat smiles as the young man orders a plate of traditional Tibetan beef dumplings called momos.

Bhat, 68, is one of thousands of Tibetan refugees whose families fled Tibet and settled in Kashmir following a failed uprising against China in 1959. Now his restaurant, Kareem's Momo Hut, is one of the most popular momo joints in Srinagar, Kashmir's summer capital that's also called Kashmir's "City of Lakes."

Bhat's family is Muslim. He says when the Chinese communist government took power in the 1950s, some Muslims were put in jail. Bhat's family came to Kashmir in part because it's majority Muslim.

Bhat was about 8 years old when he and his family first arrived in Srinagar. At first they lived in tents erected by the authorities on the city's largest Muslim prayer ground, the Eidgah. The locals weren't welcoming, says Bhat.

"They thought we were Buddhists from Ladakh," he says. "I remember a group of Kashmiri people trying to prevent us from setting up more tents. Suddenly one of our elders came in the open and read the Adhaan, the Muslim call to prayer. The hostile crowd was shocked to know that we were Muslims and their behavior instantly changed. What followed were hugs, kisses and tears. For the next few days it was these people who arranged food for us."

Ever since then, Bhat says he's never felt like an outsider. "We consider ourselves Kashmiris."

Many Tibetans who came to Kashmir in the 1950s and early 1960s have died. Only a handful of older people like Bhat remember the journey from Lhasa, the Tibetan capital, to Kashmir. When he thinks of Tibet, he thinks of a faraway land. His early impressions of that region came from his parents' bedtime stories.

Because he was young when he left Tibet, he felt that many ties to the country were snapped. But the thing that loomed large in Bhat's imagination as a young boy was the food he ate in Tibet. In their new home they still ate momos, steamed or fried dough stuffed with minced meat or vegetables, often with hot sauce. And they ate tsampa, a type of cereal often made with roasted barley flour and eaten with tea, and thukpa, a traditional noodle soup with herbs.

When Bhat was a teenager, he decided to help the community elders who were trying to popularize these foods in Kashmir. This endeavor ended up being both a way to earn a livelihood and a way to stay connected to his roots.

"It did an additional thing [too]," Bhat says. "It brought us closer to our Kashmiri brothers."

Bhat started his own small restaurant in the late 1980s. Back then most of his customers were from his own community. "Initially, Kashmiris didn't like these foods at all. They would be repelled by the thought of noodles because they would compare them with earthworms," he says with a cackle.

But today, he says, momos and other Tibetan dishes are popular. With 400 to 500 customers a day at his restaurant, including many Kashmiris, he says the food "has bonded us together."

Bhat says ever since he started selling momos, he's never wanted to do anything else in his life. "Serving momos has not just been a business for me," he says. "I think by treating my customers, whom I consider guests, in a friendly way, it gives me a strange satisfaction." If he keeps doing this work, Bhat says, he can die happy.

— Photography and interview by Showkat Nanda

From Guatemala to Mexico

The words of K'iche', her native Mayan language

Rosa Gonzalez, 54, was born in Quiché, a mountainous region of Guatemala where tiny villages dot valleys and plateaus hover 6,000 feet above sea level. In the foothills of the imperious Cuchumatanes peaks, Rosa spent her early childhood herding cows and sheep along ravines and across streams.

Back then, Rosa didn't go to school. Most of her family and friends were illiterate and spoke only their native Mayan language called K'iche'.

But in the mid-1970s, her parents — like so many other families from the Western Highlands of Guatemala — packed up and trekked eastward toward the tropical lowlands of Ixcan. The government had a program providing landless campesinos, or rural agricultural workers, with land in the jungles bordering Mexico.

The new settlements emphasized education and solidarity. Rosa learned to read and write in Spanish, the local economy was flourishing, and optimism was high.

But with its well-organized communities and remote setting, Ixcan ultimately became a springboard for the newly formed Guerrilla Army of the Poor. In the early 1980s, the Guatemalan military tried to destroy the guerrillas' support base with scorched earth campaigns, razing entire villages. About 200,000 were killed in a 36-year conflict, and most were Indigenous. Rosa's family fled to Mexico along with roughly 100,000 other Guatemalans.

After the Guatemalan government and guerrilla forces signed a peace agreement in 1996, a majority of the refugees in Mexico returned home. Rosa, who by now was married with children, begged her husband, Lucas, to remain in Campeche, Mexico.

"I saw the Xib'nel in Guatemala," Rosa says in K'iche'. Xib'nel is a mythical figure, akin to a female Grim Reaper, and brought on a fright and terror that still haunts her. "When I crossed the river into Mexico," Rosa says, "I said goodbye to my sadness."

"But," she stresses, "I can never forget my land." She has no physical keepsakes to remind her of her childhood home but does have one prized possession she always carries with her: her language of K'iche'. Rosa's 29-year-old daughter Ana María Chipel Gonzalez was born in Mexico but speaks K'iche' nearly fluently.

"Our languages and Guatemalan heritage are fundamental to who we are," says Ana María, who traveled to a nearby city to get a master's degree in tax law and has served as a representative in Mexico's National Institute of Indigenous Peoples. Mother and daughter both promote the preservation of their culture, including prompting local youth to wear traditional Guatemalan clothing.

It's normal to hear K'iche' and other Guatemalan Mayan languages on the streets of Santo Domingo Keste, the tiny Mexican town where Rosa and Ana María and other refugees from Guatemala live.

Ana María thinks of the Guatemalan community in Santo Domingo Kesté as a symbol. "The mere existence of Kesté shows our resilience, unity and bravery as a people. We must never forget this."

Ana María now has a new baby, Luca, and says she will teach him everything she knows about her parents' culture — especially the K'iche' language. As for what Ana María thinks is the most important word in K'iche'? "Nu wara'b," she says. It means "my root."

— Photographs and interview by James Rodríguez, whose work is supported by a FONCA grant

From Yemen to Ecuador

Incense stones made by his grandmother

Nader Alareqi is originally from Sanaa, the capital of Yemen. But for the past decade, the country has been in the midst of a civil war. In 2015, Saudi Arabian forces began bombarding Yemen, and that's when the 35-year-old knew he needed to go.

"It was very important to leave my country because [the war] was not life," he says.

In July 2015, Alareqi and his wife left Yemen. They first moved to Egypt, where they had a child. But Alareqi didn't want to stay because of the economic situation there.

Alareqi had heard from a few friends that Ecuador was one of the only countries where he wouldn't need a visa to enter. Alareqi, his wife and child all traveled to Quito, Ecuador, in June 2016.

When he was packing to leave Yemen, Alareqi knew he wanted to bring something special from his culture. He brought some special food and spices. (In fact, he now sells Arabic foods and spices at an Arabic food product store in Quito.)

But he also brought something else, bakhoor. In Arabic, bakhoor means fumes, and across the Arabian peninsula, people light it like incense. "You light them on fire for a good smell in your house," Alareqi says.

Alareqi's grandmother made bakhoor herself, a mixture of perfumes and scented leaves. She would mix them, heat them, and leave the liquid to dry for days. "The ones I have now have been stored for more than five years. The smell doesn't change," he says. "My grandmother did it just for my family — not as a business. These are very special stones made with love."

Alareqi says that even though bakhoor is popular in Arab countries, in his opinion, his grandmother's is the best. She used a secret recipe with a large collection of perfumes and herbs. Alareqi says the smell of lit bakhoor transports him back to Sanaa.

"It smells just like my grandmother's home," he says. "I keep remembering the old days when I was a kid and I stayed at her home."

As the eldest grandchild, he says, he was his grandmother's favorite. "She was my mom and more," he says. "I lived with her more than with my parents."

Two years ago, Alareqi was driving to work when he got a call from Yemen. His grandma had died of a heart attack.

"I stopped in the gas station and literally I cried for about half an hour," he says. "After that I stayed in the car for two hours. I didn't know where to go and what to do."

"That day I started to understand why people told me that coming to the West would be difficult," he says. "I now believe them."

And he believes that the aroma from lighting the stones works a kind of magic: When he lights the bakhoor, he feels like he's back in his grandmother's house.

— Photos and text by Yolanda Escobar Jiménez

Tell your story

We'd like to hear more stories about the objects that migrants have brought with them for sentimental reasons. If you have a personal story to share from your own experience or your family's experience, send an email to [email protected] with your anecdote and with "Precious objects" in the subject line. We may follow up and ask for a photograph so we can feature more such accounts in a future story on NPR.org.

Additional credits

Visuals edited by Ben de la Cruz, Pierre Kattar and Maxwell Posner. Text edited by Julia Simon and Marc Silver. Copy editing by Pam Webster.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDM3NjYwMjA5MDE1MjA1MzQ1NDk1N2ZmZQ004))