Historical markers are an iconic part of the American landscape. They appear by the sides of roads, in towns, at rest areas and even in the middle of nowhere.

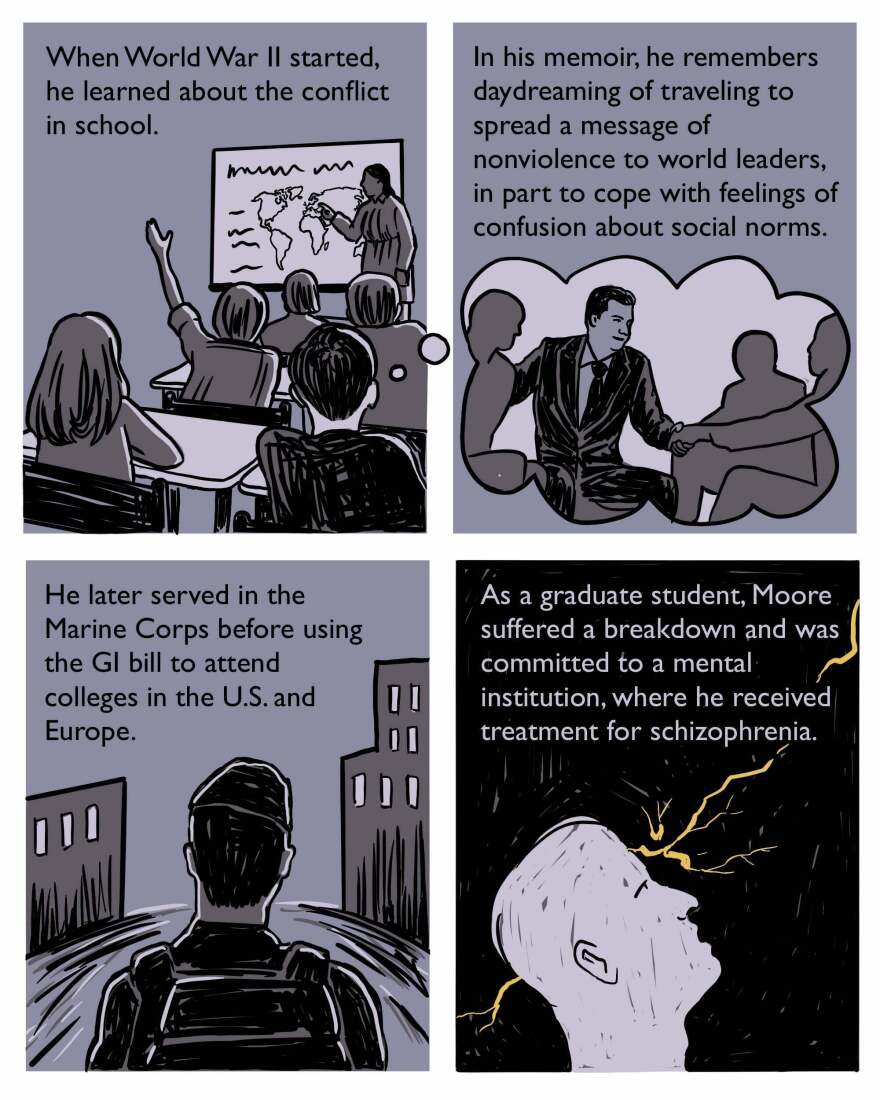

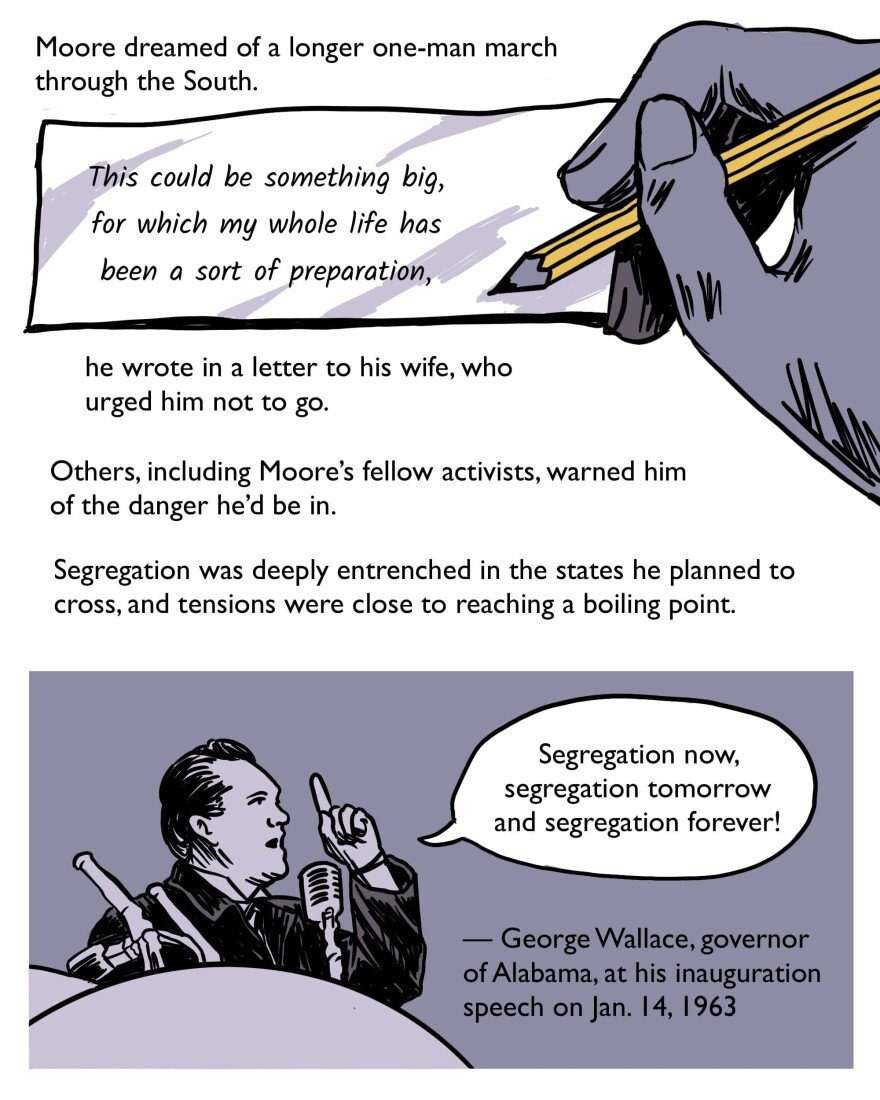

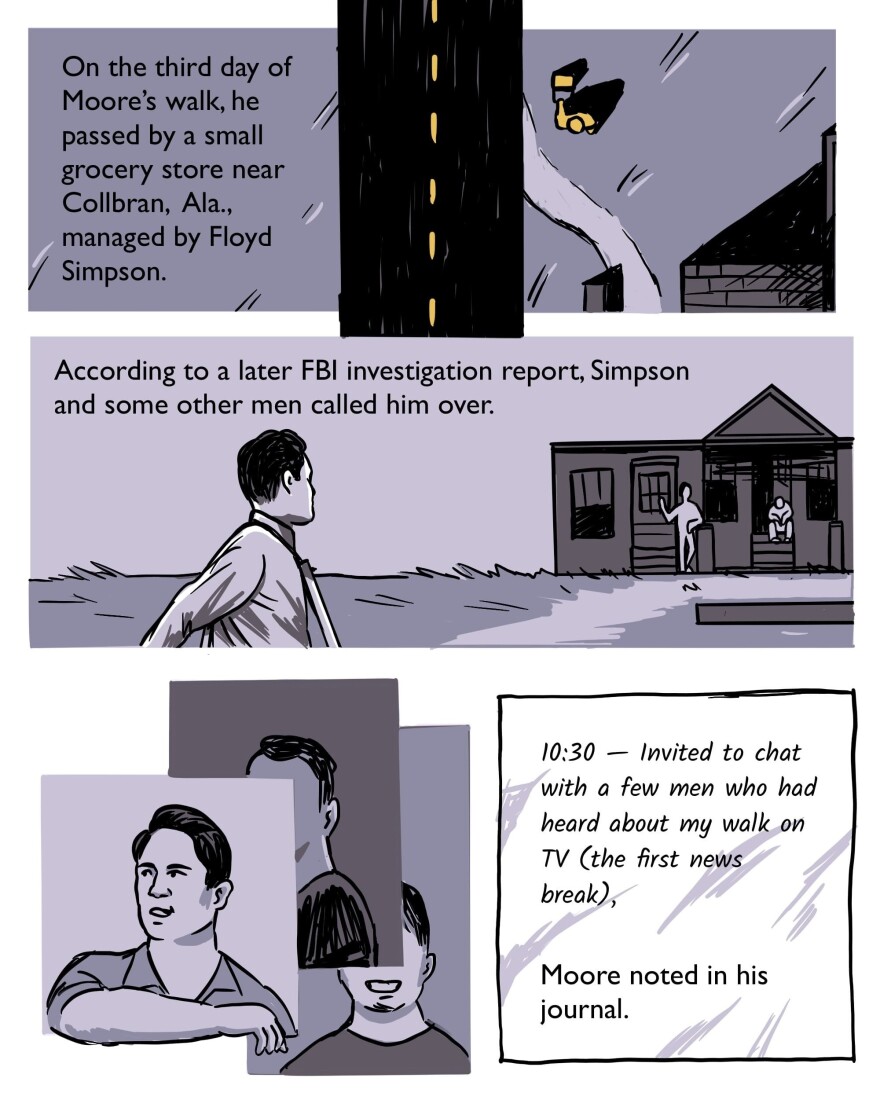

If you drive down U.S. 11, a couple of miles past Gadsden, Ala., you'll find a marker about the life and death of William Lewis Moore, who was murdered on a civil rights protest walk. The silence around Moore's murder bothered one man for years, until he started a campaign to put up a marker about it.

This comic is part of a yearlong investigation by NPR into the fractured and confusing landscape of historical markers in America.

Photo references: Press & Sun-Bulletin via AP, Laura Sullivan/NPR (2), Bettmann Archive/Getty Images (2), Frank Rockstroh/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images, Gado/Getty Images, Afro American Newspapers/Gado/Getty Images, Laura Sullivan/NPR, AP, Library of Congress, Laura Sullivan/NPR

This comic was written and illustrated by Connie Hanzhang Jin, based on reporting by Laura Sullivan and Connie Hanzhang Jin. It was edited by Emily Bogle and Robert Little, with copy editing by Preeti Aroon.

Copyright 2024 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDM3NjYwMjA5MDE1MjA1MzQ1NDk1N2ZmZQ004))