By: Paul Tait Roberts

I joined WCVE's production crew, a bottom rung full-time TV job, in 1989. VPM was then commonly known as WCVE, or Channel 23. At that time, we lived in a world where all TV pictures were standard definition (SD). But no one called it SD until years later when rumors swelled that high definition (HD) TV existed and that in some bright, colorful, crisp future, HD would replace SD. Before that, to us, SD was just TV. It was the only resolution. We thought a TV picture looked pretty good. Until it didn’t. Of course, HD did take over. Then came 4K, 8K, and who knows what’s next. Today, video professionals can actually pick a high definition resolution, based on where they want to show a video; on a movie screen, a TV, a laptop or a phone.

In 1989, every tool we used to make TV was bulky, heavy, unwieldy, unreliable, and prohibitively expensive.

My first TV training session as a crew member happened in 1988 when I was a part-timer at WCVE. My then-boss, Dave DeBarger, summoned a bunch of us TV production hopefuls into the studio for a group lesson. He began by saying, “This is a camera. It tilts. It pans. It trucks. It booms. It focuses. It zooms.” He demonstrated these functions as he listed them, with one of WCVE’s huge studio cameras.

To imagine this camera, mount a car engine on a telescoping, rolling pedestal, and attach a zoom lens so heavy, it takes 2 people to lift it. It was a behemoth, and at the time, I thought it was amazing. I would learn otherwise.

For instance, the internal electronic guts of this camera relied on three separate vacuum tubes, a technology hearkening back to the 1920s. These tubes respectively collected red, green, and blue light separately. This light was then combined through engineering chicanery to create a TV image. The problem was, these tubes were electronically unstable and required near-constant adjustment before each use. If the adjustment was off, and it always was, the picture’s color went kaflooey; tinting green, blue, or red, but usually green.

If the tubes got jostled a bit, they would come unseated in their socket. A surly TV engineer would be called in to begrudgingly reseat it and go through a complicated setup regime while cursing us for mistreating the fragile camera. Each vacuum tube cost several thousand dollars. An entire camera might cost $75,000, almost the price of my first house.

Now, take your phone out of your pocket and shoot some video. In just a few seconds you’ve produced a video unattainable and unimaginable in 1989. You made no adjustments, there was no green-tinted image, no angry engineer. Just a fabulous picture.

Our cameras needed a lot of light, like the output of the Sun, to see anything at all. In the studio, we compensated by using a lot of very bright light fixtures made by Kliegl. Our Kliegl lights used tungsten lamps, which are glorified lightbulbs. When turned on, these lamps put out a lot of light and also egg frying heat. The Kliegl’s metal housings got so hot they would sear your skin if you touched them without wearing thick leather gauntlets. I’m not exaggerating.

Among these lights, we used Scoops. These were floodlights inside bell-shaped housings. We used about a dozen scoops to wash a background curtain, or cyclorama, with colored light. To add color, we attached a lighting gel, usually blue, to each scoop. To change the color, we had to replace each gel, one by one. This task took half a day, and I enjoyed it as much as I enjoy dry, sugar-free bran flakes.

When all the lights were on, the air conditioning was turned way down to make the room bearable. This was a fight between hot and cold that only the power company won.

Today, LEDs dominate the industry. They are lightweight and they won’t heat up the room or burn your hands. Many LED lights even give you the option to change colors with a quick turn of a knob. They use so little energy that many of these lights can run on batteries. I love using LED lights, but the old Kliegls make better stories.

You’ve surely seen images of TV control rooms where producers, directors, and other technicians sit in a dark room lit only by the faint glow of a large video wall. In TV, we call this a monitor wall. The wall is often just a couple of very large flat screens that use picture-in-picture to divide the screens into many smaller pictures, which represent video sources like cameras, video playback, text generators, and video effects. These screens give producers and directors a chance to look at a video source, before putting it “on air.” Today’s monitor walls produce vivid HD images and remarkably accurate color, but it hasn’t always been this way.

Within months of getting a job at WCVE, I walked into the TV production control room to find a few strangers disassembling our monitor wall. Our wall was made up of many black and white, 10-inch-ish Cathode Ray Tube monitors. They were small but bulky, heavy, and individually mounted in large floor-to-ceiling metal racks. Many didn’t even work. Those that did often produced grayish, barely discernible pictures. Frequently, the picture vertically rolled or skewed horizontally so much that a TV engineer had to crawl behind the racks, sort through a rat’s nest of cables, and twist knobs to fix the problem. No wonder engineers were surly.

I soon found out that the strangers taking our monitors were using them on a movie set in Richmond, reassembling them into a faux 1960s TV control room for a biopic about John F. Kennedy. It turns out, our everyday equipment was from the JFK era. WCVE had used these monitors for 24 years, since its inception in 1964.

But where was video recorded and edited?

Before my time in TV, video was recorded to a 2-inch open reel analog videotape, like an RCAQuadruplexmachine. A quadruplex was about the size of a small camper trailer. It weighed 1800 lbs. I wouldn’t call it portable. It was a top-of-the-line tape machine, but editing video on it was a chore.

Years later, videotape recorders became more compact. 1-inch reel tape machines shrank to the size of a small refrigerator. By the 1970s, videocassette machines were ubiquitous and increasingly smaller (needing only two people to pick it up). Formats like 3/4” tape, Betacam, Betacam SP proliferated. In the 1990s, digital tapes, like Digibeta, replaced these old analog formats.

Editing also evolved. I’ve heard folklore that in the early days of TV, video was edited by cutting the tape with a razor blade and scotch-taping it back together. A video engineer/sorcerer would sprinkle iron filings onto the tape, and read them like magnetic tea leaves to determine where to make the edit. Later, a couple of tape machines were plugged into each other, and a tape operator would try to make edits by pushing playback and record buttons at hopefully the right time. Sometimes, edits worked out okay.

Later, one tape machine controlled another. Accuracy increased. Then, simple PCs controlled and synchronized tape machines and could make solid edits accurate to 1/30th of a second. It was a marvel of technology. Until it wasn’t.

At WCVE, around 1995, tape machines were relegated to ingesting video into computers where all editing now happened. Computer software editing was called non-destructive, or non-linear editing. Think of this as a word processor for video. Old-school tape editing was then referred to as linear editing, though no one ever called it that before non-linear editing came about. We just called it editing.

After completing a project on a computer editor, the only way to distribute it was to record it back to tape. The tape was walked down the hall and given to someone else. That person would play it back in another tape machine for broadcast. If other TV stations wanted to show the program, copies were dubbed and mailed to them. If something went wrong, you had to do this process over again.

Now, everything is digital, solid state and networked. Cameras record ultra high definition video to micro-SD cards the size of your pinky’s fingernail. Cards are plugged into a computer where footage is copied. Footage is then imported into editing software and is edited, again, like a word document is edited. Maybe animations and visual effects are added. Color is corrected. Audio is mixed. This process used to take multiple people, multiple facilities, and buckets of money to do. Now, it all can be done with just one person, with a laptop, casually sipping a Chai Latte. When a video is finished, it’s easily uploaded somewhere so people can watch it on TV, on the web, on a phone or virtually any place you can think of.

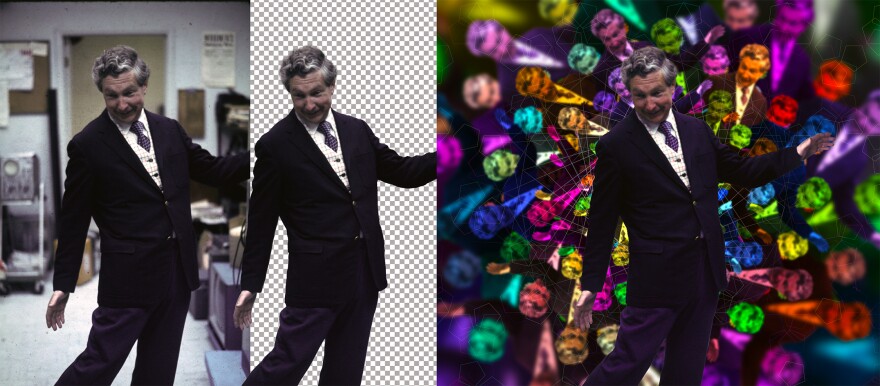

And now, we have AI as a tool. I use it in some circumstances, like in Photoshop, taking a picture and removing a person from a background, which used to take half a day to do, but now it takes seconds. But I personally draw a line at having AI create content, like scripts or imagery. I’d rather make stuff myself because I like making stuff. It’s challenging, it’s rewarding, and it aligns with VPM’s mission of having people create original content.

It seems that the things we wished we could do with video in 1989 have come true. Now, just about anyone can create a video far better than the SD content we used to make. But now, perhaps ironically, we also have fantastic software that can make our beautiful UHD video look like glitchy, fuzzy old SD.

It’s so easy to produce good video now, compared to 1989, that sometimes I feel like I’m cheating. I admit, having limited and subpar TV tools at our disposal pushed us to be more creative. But, having only limited and subpar TV tools at our disposal hampers bringing our ideas to fruition. The fantastic, ultra-high-definition tools we use today are only limited by our understanding of how to use them and our own creative concepts. I can’t wait to see what’s next.