In 1830, a group of Virginians gathered to write a new state constitution that would allow more white, male property owners to vote.

Alexander Campbell arrived at the convention to represent what is now the panhandle of West Virginia. He watched in frustration as slave-holders from the eastern part of the state undercut those modest reforms by carving out state legislative maps that gave them lasting political power in the General Assembly, according to historian Brent Tarter.

Campbell later groused that Western Virginians were treated like “demi-slaves, or an Irish peasantry,” in an episode Tarter recounted in his 2019 book“Gerrymanders: How Redistricting Has Protected Slavery, White Supremacy, and Partisan Minorities in Virginia.”

The biggest losers of all were the actual slaves -- the first of several instances in Virginia where a minority of white, male elite -- and later, black lawmakers themselves -- extended their power through gerrymandering.

This year, with Virginia’s black caucus larger than at any point since Reconstruction, several African American lawmakers are pushing to changes to generations of gerrymandering by giving minority citizens a bigger seat at the table.

At a press conference on Tuesday, Del. Marcia Price (D-Newport News) laid out a proposal for a citizen redistricting committee that would draw new Congressional and legislative districts every ten years. She said it would prioritize including communities of color throughout the redistricting process.

“I would like to end racial and political gerrymandering and get to fair community-based maps,” Price said.

Price’s bill isn’t the only option on the table.

There’s also a proposed constitutional amendment that passed last year with bipartisan support. Lawmakers need to sign off on it again this year for it to appear on the ballot in November.

Both plans are a big change from a long history of legislators drawing their own districts.

“This is a really important year,” Tarter said in an interview last week.

The current debate over gerrymandering has its roots in slavery, according to Tarter. It begins with what he calls the Great Gerrymander of 1830, which gave extra power to the eastern parts of the Commonwealth, where slavery was most entrenched.

“It was quite clear at the time that that Great Gerrymander was created in order to protect the interests of slavery and slave owners,” Tarter said.

Later, after the Civil War, white lawmakers restricted the voting ability of blacks through voter suppression tactics. They also drew legislative maps that favored southeastern Virginia, where there was strong support for segregationist Jim Crow laws, according to Tarter. While these gerrymanders benefited segregationist Democrats, the motives weren't partisan."

“It benefited an interest,” Tarter said. “It benefited the interests of white supremacy.”

That system fell apart in a series of lawsuits and legislation passed in the 1960s, including the Voting Rights Act.

The General Assembly’s Democratic majority, hungry for votes amid Republican gains, cast aside its explicit segregationist platform and began courting black voters. In subsequent decades, both Democratic and later Republican majorities carved out relatively safe districts for African American lawmakers, according to Tarter.

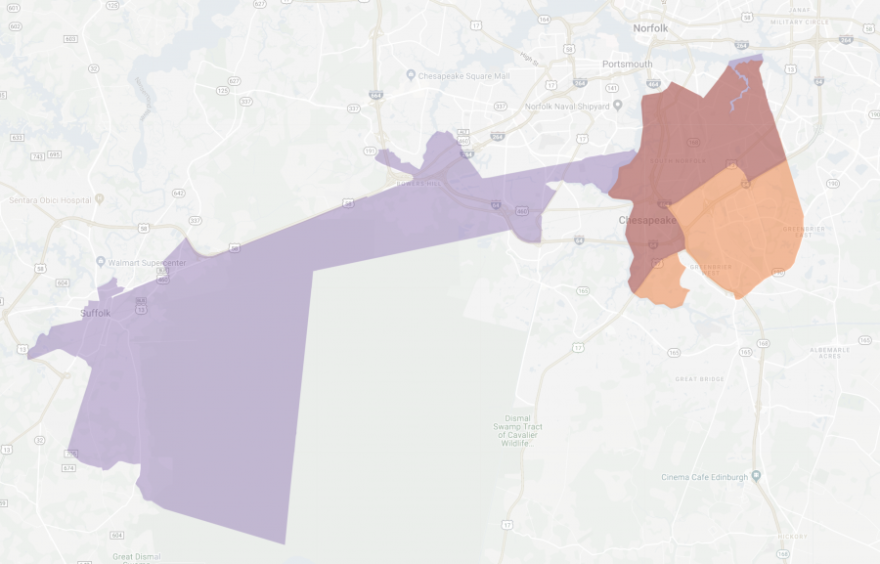

In the last round of redistricting in 2011, House Republicans who controlled the lower chamber mapped roughly a dozen safe House districts for black Democrats by packing high percentages of African-American voters into their districts. The Republican plan passed with broad support from black Democrats. But it had a side-effect.

“By packing more black voters into those districts, it meant that the neighboring districts became whiter,” Tarter said.

In 2018, a federal court ruled that the practice unconstitutionally diluted the voting power of African Americans. Price said the 2019 elections, where black lawmakers like Del. Josh Cole won in majority-white districts, showed lawmakers didn’t need districts concentrated with black voters to get elected.

“I think that it is now up for us not to protect my specific power here in the legislature, but that of the African American and communities of color,” Price said.

Price and most other black delegates voted against the proposed constitutional amendment last year. It would create a 16-person commission made up equally of lawmakers and citizens. Critics are worried the amendment could give too much power to the Virginia Supreme Court and not enough to minority voters.

But Price’s bill doesn’t change the constitution, meaning lawmakers could choose to ignore it. Price said she’s planning to introduce a new amendment next year.

Sen. Mamie Locke (D-Hampton) said lawmakers shouldn’t give up on the redistricting amendment passed last year, though she said she’s open to Price’s plan too. The amendment, unlike Price’s bill, couldn’t be rescinded at the whims of lawmakers if it passes the legislature this year, and with voters in November.

“If you scrap the amendment this year, then you have to wait another year to start it all over again,” Locke said.

Locke is co-sponsoring legislation that tweaks the amendment. It adds requirements that the commission reflects Virginia’s diversity, and sets out guidelines for the Virginia Supreme Court. Unlike the amendment itself, the legislation could easily be taken out of the code by future General Assemblies, which is one of several reasons Price said she put forward her own legislation.

One way or another, Locke thinks Democrats need to make good on their past promises to end gerrymandering, even as some in the party appear squeamish to give up their map-drawing powers after sweeping both chambers of the legislature in November's elections.

“Why now, when we're in the majority, are we having cold feet about this process?” she said.

Both proposals will be up for votes in the coming weeks. If a plan passes this year, it will shape Virginia’s political map for a decade and beyond.

Price said the differences are healthy and can be bridged.

“African Americans are not a monolith,” she said. “We come with a diversity of thought.”