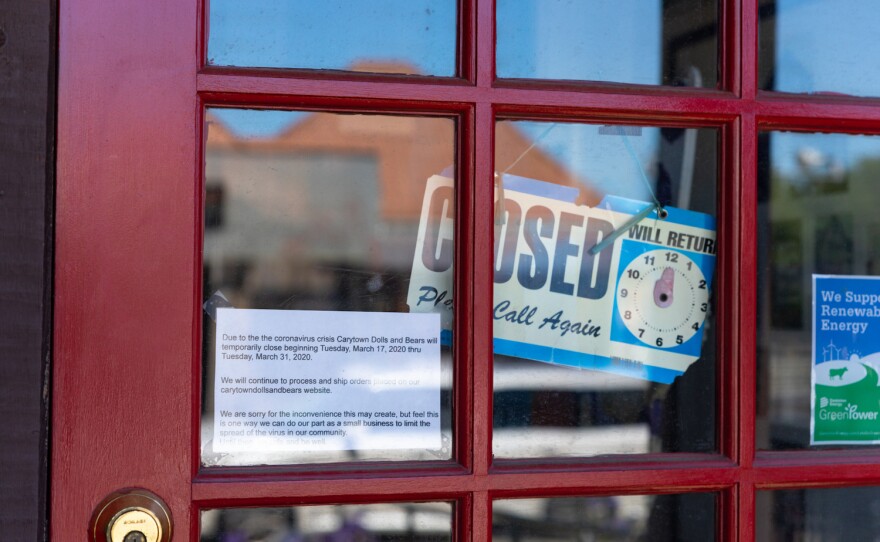

Business owners in Virginia faced waves of challenges over the last year and a half: lockdowns, health risks, staffing shortages and access to funding.

But a state grant program meant to help small businesses and nonprofits didn’t reach all applicants equally. On average, Black business owners received less than half as much funding as white entrepreneurs from Rebuild VA, the state’s pandemic grant program, through January 2021.

Experts say the pattern reflects broader trends in business ownership and investment. Rebuild VA grants require businesses to submit eligible expenses, like payroll, for reimbursement. Black businesses in the U.S. bring in average revenues that are one-sixth the amount of non-Black businesses, according to research from the Brookings Institution. Black entrepreneurs are less likely to get bank loans and more likely to rely on high-interest credit cards after a long history of discrimination by financial institutions.

The trend has continued since business as usual ground to a halt in March, 2020. The first round of the federal Payroll Protection Program came under fire for overlooking Black businesses. The pandemic has highlighted historic underinvestment in Black communities and Black businesses, said Andre Perry, a senior research fellow at the foundation.

“We never get the opportunity to scale up,” Perry said. “The data that you see around who got COVID relief funds is really a reflection of how we value people, how we value suffering. Some people's suffering is worth more than others.”

There are some indications that Black business owners have persisted in spite of tough conditions. One national study from the Kauffman Foundation found rising rates of Black entrepreneurship, a trend several experts say is playing out locally.

Still, there’s lots of room for growth. A recent report from Next Street and Common Future found that Black residents make up 29% of the greater Richmond’s population but just 5% of the region’s employer-owned businesses. The study found unmet needs for Black and Latino business owners ranging from capital to back-office help.

Carol Reese, a strategic consultant who helped author the report, envisions a number of fixes to the situation: one-stop shops for microbusinesses to find affordable specialists in areas like accounting; increased collaboration among banks, government, and local business organizations; and doing away with lending practices she believes lead to discriminatory outcomes, like ruling out borrowers based on their credit scores.

“I believe this is systemic,” Reese said. “Until this policy changes and system changes, we're going to be in this continual loop.”

Policies delivered more money for white business owners

Roughly 95% of Black-owned businesses were ineligible for the first round of PPP loans because they don’t have any paid employees. Subsequent research found a majority of Black businesses that succeeded in getting loans did so through online banking institutions that automatically vetted candidates, leading some researchers to conclude racial bias played a role in pushing Black entrepreneurs online.

The money was desperately needed. One study estimated 40% of Black-owned businesses closed in the first months of lockdown, double the rate of white-owned ones.

Reese has experienced some of the financing problems firsthand. Her consulting business was ineligible for that round because her only employees at the time were contractors. A second round of PPP loans was open to sole proprietors and reached a more diverse pool of entrepreneurs. But Reese said the bank she was working with ran out of funds. And because she has an office in a relatively wealthy ZIP code in Glen Allen, Reese found herself locked out of a federal loan program offering grants of up to $15,000 for businesses located in low-income areas.

State officials have touted Rebuild VA’s success in reaching businesses left out of early federal grants. Almost a third of the $120 million worth of grants doled out through January went to minority-owned businesses and 49% went to businesses located in low-income communities. Two-thirds of grantees through January were woman-, minority-, or veteran-owned businesses, according to Gov. Ralph Northam’s office.

Public records obtained by VPM show white and Black-owned businesses were approved for grants at similar rates during that period. But while Black-owned businesses got an average Rebuild VA grant of nearly $19,500, white-owned businesses received more than double that on average. The pattern held to varying degrees among businesses with similar numbers of employees.

Over 28% of applicants checked a box saying they didn’t wish to provide racial data or left that portion of the application blank.

Officials waded through over 20,000 applications last year before ultimately awarding roughly 3,000 businesses with grants as large as $100,000. Businesses in low-income neighborhoods -- along with complete applications -- received priority, but that preference sometimes led to outcomes policymakers may not have anticipated.

The Commonwealth Club, an all-male private club that didn’t admit its first Black member until 1988, received $100,000 from the state and $814,633 in forgivable PPP loans. The club, like much of downtown, eastern and southern Richmond, falls within an area that’s been designated as low-income under criteria set by the IRS. The club did not respond to requests for comment.

Several Black-owned businesses within a mile radius of the club had their applications denied or weren’t granted funding before the money ran out. Reese was also among those rejected from Rebuild VA and said she never found out why; state records list her application as incomplete.

In August, lawmakers approved another $250 million to replenish the program’s funds. But Reese says she has no plans to apply again, citing the time-intensive application process and lack of communication from officials.

“I’m over it at this point,” Reese said.

Amy Brannan, a program manager overseeing Rebuild VA, acknowledged her team was “a little bit overwhelmed” with the volume of communication from business owners. When the program stopped accepting applications in December, a survey on its website was flooded with hundreds of business owners asking what happened to their cases and saying they urgently needed funding, according to public records obtained by VPM. Brannan said her team has since added a three-person customer service team.

Brannan said the state is prioritizing the backlog of existing applications as it distributes the next round of money. Program staff are currently reviewing applications submitted on or before Oct. 26, 2020. Brannan declined to comment on the disparities in grant funding aside from saying the awards were based on three months of recurring expenses plus one-time COVID-related expenses like masks.

States have taken different approaches toward pandemic grant programs and reaching diverse audiences. California offered its application materials for its program, CalRelief, in 18 languages. Pennsylvania set aside over 50% of its grants for businesses owned and operated by persons who are Black, Hispanic, Native American, Asian American or Pacific Islander on the grounds that they’d been historically disadvantaged. Perry said that kind of targeted relief needs to be more widespread.

“We need to establish a reparative culture in this country that says, ‘Hey, I'm going to invest in places and in people that did not get investment because of policy,’” Perry said. “And that looks like investing in Black people.”

Some entrepreneurs saw benefits from a ‘pandemic pause’

For some Black business owners, the pandemic offered an unexpected time to expand their business or find new opportunities, sometimes with the help of state funds.

Richmond-based floral designer Brom Hansboro got about $20,500 from Rebuild VA on top of funding from the PPP program, the city of Richmond, the home improvement chain Lowe’s and the Metropolitan Business League. The cash infusion helped him ride out the suspension of weddings and embrace new opportunities like the funeral business.

On a personal level, the slowed speed allowed him to reconsider his priorities and even lose 120 pounds. It allowed him to consider the toll of burnout after spending the previous six years building a business in an industry — and city — that has not always been welcoming to Black men despite designs that have won international acclaim.

“The pandemic gave me necessary time to slow down the vibration, slow down the expectation, slow down the demand -- there was literally no demand,” Hansboro said. “When things opened up, it was a floodgate.”

Business has also been brisk at the Beet Box RVA juice bar since personal trainer and gym owner Antione “Roc” Meredith and Ashley Lewis, his former client, opened it on Cary Street in October 2020. The shop riffs on its namesake vegetable with murals, hip-hop music and a growing menu of juices and food. Whatever they’re doing, it’s working. With five stars on Yelp and legions of loyal fans, Beet Box is now planning on opening a second location in December.

“I didn't expect for us to grow as fast as we are, but I welcome it,” Lewis said.

With its perch on the edge of Richmond’s Fan district and Carytown, Beet Box attracts a diverse clientele. But Perry’s research with his peers at Brookings suggests not all businesses are able to do that. It found that Black, brown and Asian-owned businesses had on average higher Yelp reviews than white-owned businesses, but experienced slower revenue growth if they happen to be located in a majority-Black neighborhood.

“What that means for me is Black, brown, Asian businesses are worthy of investment, but they're just not getting it,” Perry said.

In Perry’s vision, cities and states would set goals for scaling up Black businesses. “If we really want to see growth in Black businesses, it means we're gonna have to invest in them,” he said.

Editor’s Note: VPM received a loan from the Payroll Protection Program.