Over the past year, VPM News has been looking into a hidden type of debt affecting thousands of Virginia college students. It’s not federal student loans – which dominates most of the headlines. It’s money owed directly to institutions, called direct-to-school debt.

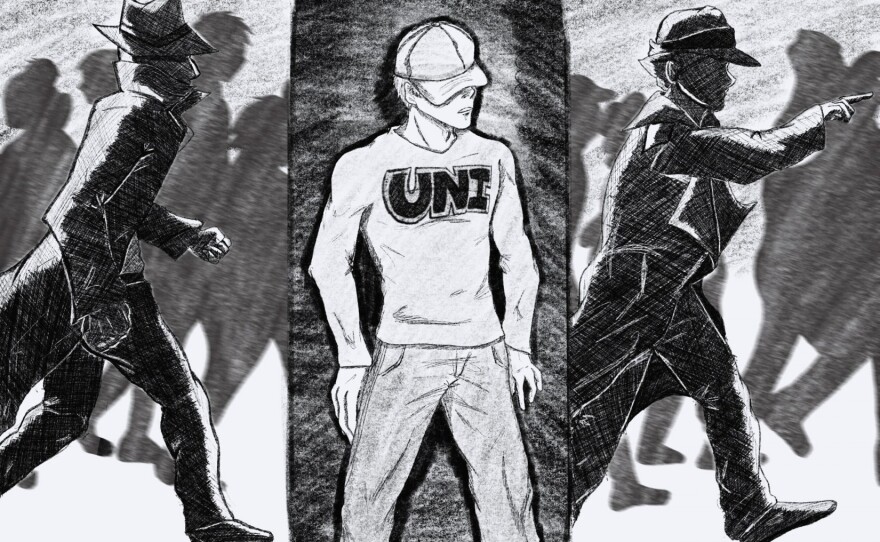

In our series Dreams Deferred, we’re exploring how this debt is creating hardships for students, making it difficult for them to complete their degrees and advance their careers. Today we’re exploring state policies that perpetuate this problem.

If you missed pt. 1 of our series, click here to read it. Read pt. 3 here. Click here to read about how we reported this series.

Joshua Bowser was summoned to an April court hearing this year in Chesterfield County by the Virginia attorney’s general office from his home in New Jersey. It was a debt collection case: the state alleged he owed unpaid tuition and fees for the two semesters he attended at Virginia State University starting in fall 2012.

“I had no idea that I even owed money,” Bowser told VPM News in a May phone interview.

Bowser called the court on the date of his hearing, and said he was contesting the debt. He was required to be there in person. Bowser, who now lives in New Jersey, says he couldn’t take time off from work to make the drive to Virginia. He also couldn’t afford to hire an attorney.

Bowser says he also had a hard time getting in touch with the AG’s office, and once he did, was told he’d have to pay off half of the balance up front in order to set up a pre-judgment payment plan. He couldn’t afford that.

It was also unclear how much he owed. The figures in court paperwork don’t seem to add up: one document indicates the balance is $6,899.50 but the warrant in debt says he owes $10,652. Bowser says he and his mom have been calling the university to try to get to the bottom of the situation, but haven’t reached anyone. VSU wouldn’t clarify the discrepancy. Meanwhile, the principal balance now includes thousands of dollars in interest and fees.

A default judgment was awarded against Bowser and in favor of the state in September.

“It’s like playing a rigged game,” Bowser said. “I don’t feel like it’s fair at all.”

The AG’s office said in an email statement they follow a “guiding principle” of considering the unique circumstances and income level of each individual “whenever possible.” But a letter the AG’s office says they always send before taking court action states that “suit may be instituted against you without further notice unless you satisfy this debt within ten days.” There's also no mention of any available payment plans in the letter.

And other VSU students told VPM News they felt pressured to pay off the majority of their balance immediately.

Bowser says he has been working two jobs, including an overnight shift at Home Depot, for most of the pandemic. Until recently, he says he was living with his parents and contributing to household expenses. These factors have added to his frustration about being summoned to court in another state — seemingly out of the blue — during a global pandemic.

“It's COVID, you know. People were trying to maintain jobs,” Bowser said. “And it's something from eight years ago that I was unaware that even existed.”

Bowser says he enrolled as an out-of-state student at Virginia State University because his cousin was going to school there, too. He says he enjoyed his time there: he says college helped him mature and become more self-sufficient.

But he had to drop out after his first year because he says his parents could no longer afford to keep helping him pay for school.

Even though a Pell grant and federal student loans covered the cost of his tuition, he still had to pay over $1,500 in university fees, $1,932.00 for an on-campus meal plan and $3,300 for on-campus housing in the fall 2012 semester alone.

“It’s expensive,” Bowser said. “That's the whole reason why I left.”

Going after vulnerable students

A VPM News analysis of court records found that between April 2020 and April 2021 — during a global pandemic — the attorney general’s office sued to collect years-old tuition and fees from over 150 Virginia State University students. They also attempted to garnish several students’ wages. The balance due in most cases was between $3,000 and $5,000 before fees.

The attorney general’s office adds a 30% attorney fee in these collection cases, which can add hundreds and even thousands of dollars to the original bill. The office also charges interest going back to the initial default date, even though many of these VSU collection cases idled for years — sometimes over a decade — before landing in court.

“That’s ridiculous,” said James Tierney, former attorney general of Maine, Harvard law lecturer and founder of State AG, an educational resource on the office of the state attorney general.

“This is where the government has to come in, I think, at some level and make a real cost-benefit analysis,” Tierney said. “If you're just shuffling people around, I mean, you give them a stimulus check on Tuesday, and you take it all back on Wednesday...what are we doing here?”

Outgoing Virginia Attorney General Mark Herring has tried to tackle some debt issues facing students. For example, he’s pursued legal action against predatory for-profit schools. But his office hasn’t addressed direct-to-school debt.

In March, Virginia Attorney General Mark Herring touted legislation he helped author in 2020 that protected Virginians’ stimulus checks from being garnished by private debt collectors during the pandemic.

“Virginians should not have to worry about creditors or debt collectors taking all of their much-needed stimulus money,” Herring said in a March 17 statement.

But by the time Herring made those remarks, his own office had filed more than 120 debt collection lawsuits against Virginia State University students since the start of the pandemic, a VPM News analysis shows.

Court records analyzed by VPM News showed that students from Virginia State, a historically Black college and university, were disproportionately represented in lawsuits filed by the AG’s office for the collection of tuition and fees during the pandemic.

The AG also took some students from Northern Virginia Community College and William and Mary to court during the pandemic, as well as students taking part in the Virginia National Guard State Tuition Assistance Program.

Several VSU students told VPM News they didn’t even know about their court hearing because paperwork was sent to an incorrect address. It’s considered legal service for a sheriff’s officer to post the notice — called a warrant in debt — on someone’s front door; they don’t have to guarantee someone lived there or was aware of it. This is how the majority of VSU students taken to court during the pandemic were notified of their court hearings.

A VPM News analysis of court records found that some VSU students who did know about the hearing weren’t able to make it to court due to lack of transportation or an inability to take the day off from work. None of the students were represented by an attorney.

Because of these issues, most VSU students didn’t attend their court hearings. Therefore, the majority of cases resulted in default judgments in favor of the state.

Meanwhile, Illinois and Colorado ended wage garnishment through most of the pandemic. And in New York, the governor and attorney general suspended the collection of all state debt collection — including student debt — through April 30, 2021 after a group of advocates and attorneys urged them to halt student debt collection.

A mandate to ‘aggressively collect’

Empowered by a Virginia law dating back to the 1980s that specifically requires state agencies to “aggressively collect” debts, the Virginia attorney general’s office routinely files debt collection lawsuits on behalf of state agencies, including public universities, sending a contradictory message about the state’s goal of becoming the “best state for education” by 2030 with a focus on equity.

The attorney general’s office keeps debts on its books indefinitely, sometimes attempting to collect multiple times through the court system. If they can’t collect immediately, they wait until someone gets a new job, tries to buy a home — or refinance a home — to collect again. And even if someone dies, the state can keep a lien on their house, according to Virginia’s legislative review commission.

State agencies have other special collection powers, like the ability to withhold state tax refunds and other services — like college transcripts — as a form of debt collection. And since they’re not officially considered debt collectors under the federal Fair Debt Collection Act, additional consumer protections don’t apply in these cases.

A 2019 state report on the operations and performance of the AG conducted by the state-funded legislative research group JLARC found that the office “has established a reasonable process for pursuing debts” and is “incentivized to pursue most debts because it relies on commissions from successful debt collections to pay for debt collection services.”

According to JLARC, “the goal is to get a judgment soon, because by law they are supposed to aggressively collect. If the debtor doesn’t pay soon, they have to proceed to litigation in most cases.”

JLARC only interviewed state agencies as part of its report, not individuals being pursued over the debt, according to Mark Gribbin, JLARC’s chief legislative analyst.

The AG’s office did not commit to an in-person or virtual interview after months of repeated requests to speak with their debt collection staff about operating procedures and more. In emails, the press office repeatedly downplayed their involvement in student debt collection. Press secretary for AG Herring’s office Charlotte Gomer wrote that they’re “only one player, and really the last line, in the Commonwealth’s debt collection system” and insisted that schools arguably play a much larger role in debt collection.

Gomer also wrote that, “the General Assembly, rather than the OAG, has made the Financial Recovery Section the collections entity of last resort for recovering this money.” But former AGs have taken a different view, even working to strengthen the office’s involvement in collections by helping draft legislation to further cement its role in this process.

In the early 2000s, Del. Chris Saxman worked with then-Attorney General Jerry Kilgore to pass legislation requiring debts of $3,000 or more and over 60 days past due to be turned over to the AG’s office for collection. The legislation also allowed the AG to “retain as special revenue up to 30 perecent of receivables collected on behalf of state agencies” which the office now calculates after attorney fees are added.

“We were trying to make our debt collection unit run more like a business,” Kilgore said in a 2020 interview with VPM News. “This was a way to fund that particular unit in the AG office without going to the General Assembly every year to ask for more money.”

Even with a state-sanctioned mandate to aggressively collect, Georgetown University law professor Heidi Feldman, who teaches a course about the historic and modern role of state AGs, says, “how aggressively they pursue debt collection is going to be partly discretionary.”

Feldman says there's no other attorney in state government with so much independence to define their priorities and the mandates they want to pursue to serve the public interest. But she says what’s changed over time is an understanding of what constitutes the public interest.

“If you serve the public, and part of the public are people struggling to pay for their education, then you would want your state attorney general to take that into account in thinking about collecting those debts,” Feldman said.

“It’s not that you couldn’t give a public policy reason for defending the aggressive measures. But what we’re talking about here is figuring out just how aggressive the measure is. And the more aggressive the measure is, and the more vulnerable you think the debtor is, then the question is, does that really serve the public interest?”

‘I want some answers’

Kevin Davenport, VSU’s vice president of finance, was surprised to discover that the state had continued to pursue his students in court during the pandemic. Many cases were from nearly a decade ago.

“I want some answers on that myself,” Davenport told VPM News in a September 2021 interview. “The state and the attorney general, they all know what we're struggling with as an institution. Why in the world would you be going out to collect from Virginia State students? I just don’t know. The only thing I can think of is there's somebody there making a bad decision, and that somebody ordered that and for the wrong reasons.”

Virginia State University is an HBCU about 30 minutes south of Richmond. Founded in 1882, it was the only public university in Virginia that served Black students until the 1950s. Today, over 70% of VSU students receive federal Pell grants, which are designed to help low-income students attend college.

Despite the financial needs of VSU’s student body, the school doesn’t have nearly as much endowment money to help subsidize the cost of students’ tuition and fees. Virginia State’s endowment funds were about $57.4 million in the 2019 fiscal year. That’s compared to an endowment of over $7 billion at the University of Virginia and over $2 billion at Virginia Commonwealth University for the same year.

Davenport wanted to make it clear that VSU itself was not pursuing students for past-due tuition during the pandemic. He stressed that the school is using federal COVID-19 relief funds to pay off outstanding balances for students currently enrolled, from fall 2020 through fall 2021. But that funding won’t help students like Joshua Bowser and others who were taken to court by the attorney general’s office during the pandemic.

Davenport would like to see the state forgive those debts, because he says VSU can’t afford to.

“I'm trying to run a business just like everybody else is. So my thing is, if the Commonwealth wanted to do that [forgive VSU debts], fine, we would do that. But I don't have any money to do that,” Davenport said.

Meanwhile, Virginia State University students like Ardell Crane can’t finish their degrees because of direct-to-school debt. Crane’s account was also litigated in fall 2020 by the Office of the Attorney General for $3,976 in tuition and fees, $1,192.80 in attorney fees, and 6% annual interest that started accruing in February 2018.

Despite serious medical issues and a felony record, Crane has completed a master’s program in career and technical studies from Virginia State University and was working on his second master’s degree in educational administration and supervision in 2017. He planned to graduate in May 2017, but ended up owing money to the school for classes he couldn’t attend while hospitalized in spring 2017 for reconstructive surgery on his esophagus. He says he swallowed lye at the age of two, does not have a voice box, and has been unable to qualify for disability benefits.

Crane has been unemployed for most of the pandemic and can’t afford to pay off the balance.

He's in his 50s, but says he became determined to complete his education while incarcerated. And while the felony conviction has made it hard to find work, he wants to finish his second master's and remains hopeful.

Despite all the challenges he’s faced, Crane has started a successful business with his wife and hopes a second degree could help him achieve some big dreams.

“I would love to have that title of project manager, working with some big corporation with a decent salary,” Crane said. “I would love that.”

Current law and regulations don’t allow schools to discharge debts without approval from the AG. When requesting a debt discharge, the AG requires schools to indicate that they’ve made an intensive effort to collect. Schools do have some flexibility, though, when it comes to how they work with students with direct-to-school debt — and how they set policies that can contribute to students ending up with the debt in the first place. That’s tomorrow in our series, Dreams Deferred.

If you missed pt. 1 of Dreams Deferred, click here to read it. Read pt. 3 here.

Learn more about how we reported this series.

Reporting for this series was made possible through a ProPublica Local Reporting Network fellowship VPM News reporter Megan Pauly received in fall 2020.

Dreams Deferred was reported by VPM’s Megan Pauly with editorial guidance and production support from VPM's Sara McCloskey, David Streever, Connor Scribner, Elliott Robinson, Travis Pope and Ben Dolle.

Additional support was provided by independent contractors Johanna Zorn (editor) and Amy Tardiff (fact-checker). Special thanks to: ProPublica’s Alex Mierjeski, Maya Miller, Beena Raghavendran and Annie Waldman.