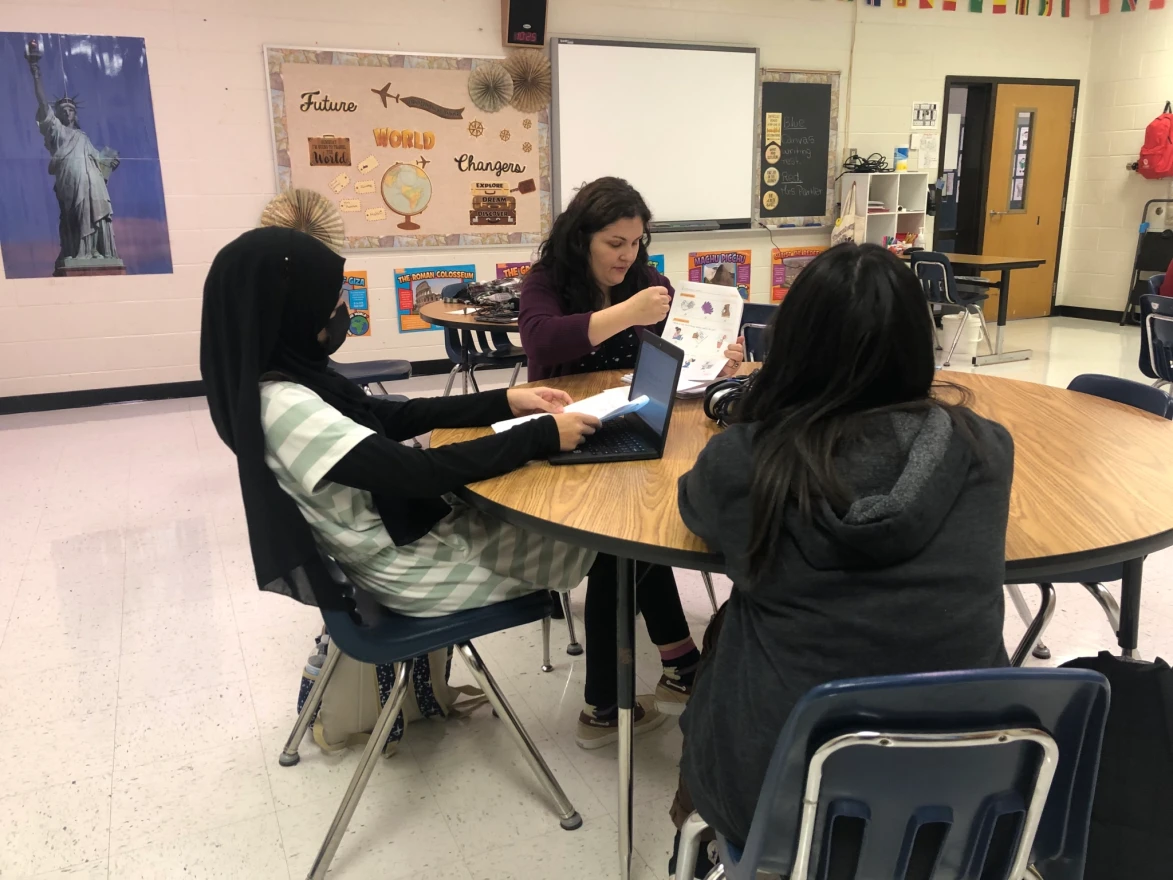

A student laughed as Fabiana Parker flipped orange flash cards to reveal silly portraits corresponding to emotions: silly, bored, angry, sad. Parker uses these cards to teach newcomers to the English language learning program at Thornburg Middle School.

Walking through the school hallways, it is easy to see why Parker is Virginia’s 2023 Teacher of the Year. Students crowd around her to wish her a good morning and chat with her before classes start. Teachers credit her for giving them a new understanding of English language learners (ELLs). Parker has a connection with students overcoming the language barrier — because she was once an English learner, too.

Originally from São Paulo, Brazil, Parker’s family moved to London when she was 15 years old. Unlike her students, she didn’t have a teacher dedicated to helping her learn English and acclimate to her surroundings. Going through those obstacles as the only Brazilian in her classes kickstarted her passion for teaching and language learning. Parker started her career as a Spanish teacher in Boise, Idaho, but later transitioned to being a teacher for the English Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) program when she moved to Virginia.

“There was always the fear, ‘Oh, maybe my English is not good enough,’ even though I had gone through college,” Parker said.

Now, her days start with teaching all levels of language acquisition in Spotsylvania County at Thornburg Middle School before driving to Spotsylvania High School after a brief lunch break. There, she has her own classes for students closer to exiting the English language learning program. Schools might use ESOL teachers in two ways: assisting ELLs in a class with native speakers or teaching their own classes with only ELLs. Parker does both.

In total, she educates 66 students from 6th through 12th grade, but she says that is not nearly as chaotic as managing the 110 students she had in Culpeper County. Overall, the number of ELLs has increased by 20% statewide, according to the Virginia Department of Education. But VDOE noted that both Spotsylvania and Culpeper counties have seen a 75% and 82% increase in ELLs, respectively, in the past five years.

The number of ELLs has increased in Virginia as the state has accepted more Afghan refugees and people from countries such as El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras continue to migrate to escape poverty and violence.

“Although Virginia does a good job educating ESOL students, it could be much better,” Parker said. “Other states spend a lot more money on the ESOL program than we do, and I think as the population has been growing we have struggled to keep up.”

In terms of spending, Virginia has the worst gap in the country in state revenue — 48% less — per student between districts serving the most and fewest ELLs, according to a report from nonprofit the Education Trust.

Four bills were introduced at the General Assembly this session to alleviate that funding need for ESOL teachers. Del. John Avoli (R–Staunton) and Sen. Ghazala Hashmi (D–Richmond) are leading the bipartisan effort to establish college and career readiness programs for ELLs as well as incentive grants for teachers who earn an ESOL endorsement. While the House of Delegates rejected Avoli’s proposals, Hashmi’s identical bills, SB 1109 and SB 1118, unanimously passed the Senate on Feb. 6.

Beyond learning a language

SB 1109 would give annual reimbursement grants (up to $500 per ELL student enrolled in high school) to any school division to expand access to college and career readiness. The Virginia Board of Education is required to prioritize grants for school divisions with less than 3,000 students or poverty rates above 20%. Hashmi’s impact statement estimates that the maximum amount of grants would cost $14,400,500.

Michael DeAlmeida spoke about the corresponding House bill, HB 1823, during an event held by the Virginia Coalition for Immigrant Rights on Jan. 11. DeAlmeida is currently a member of the student assembly at Richard Bland College. He credits his educational success to the ESOL courses he took at Hermitage High School. When DeAlmeida started high school in 2018 there were 130 ELLs, but now 221 students are part of the ESOL program at the Henrico County school, according to VDOE.

“I happen to be taking honors English today in college thanks to the great ESL system that I had in my high school,” DeAlmeida said. “So, it's really crazy for me to think about how when I came from Brazil in 2018, I could only speak three things, ‘Hi, how are you and bye.’ I couldn't write a sentence. I couldn't speak.”

He said these bills can help current ELLs not only acquire new language skills but also find a sense of community — as he did.

“This is not just a matter of ESL education, but general education,” he said. “Just think about it like this: If those students cannot learn English at those high schools, how do we expect them to succeed past those SOLs, be able to take AP courses or college preparatory courses, graduate and go to college?”

Virginia schools require all students to pass five Standards of Learning tests to graduate. ELLs have to meet this requirement before they turn 21, which Parker says puts older students who migrate at a greater disadvantage to graduate.

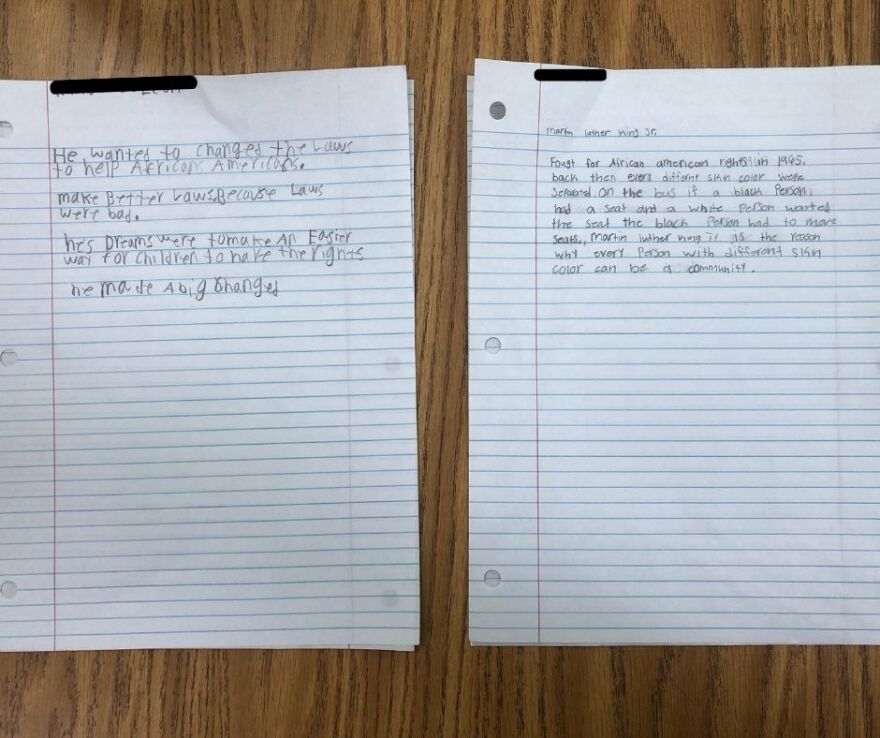

In the 2021-2022 school year, ELLs had low SOL pass rates: 32.29% passed the English reading test, 18.46% passed the English writing test, 29.88% passed the history and social science test, 36.13% passed the math test and 19.86% passed the science test, according to VDOE. During the same school year, 24.63% of ELLs dropped out of schools across Virginia.

Finding a path that accommodates ELL students who have overcome hardships is essential, Parker said.

Katian Corado, one of Parker’s former students, credits her for helping her finish her high school degree after getting pregnant. Corado immigrated to Culpeper County from Guatemala when she was 14 years old and got pregnant during her junior year. She wanted to drop out, but Parker helped modify an education plan to secure a high school diploma, Corado said. She recalled the moments in which Parker calmed her tears of frustration when she couldn’t grasp the English language.

“She earned my heart from the first moment I met her,” Corado said.

While Corado would have liked to attend university or community college, school administrators were not equipped to help her navigate the process as an undocumented immigrant, she said.

“They were like, ‘Oh OK, forget it,’ and they wouldn’t say anything else, wouldn’t give me another option or say, ‘Look, you have this option since you don’t have a Social Security number,’” Corado said. “Then, I felt very sad because I would have liked to continue studying after I had my baby.”

Although she didn’t get to further her education through conventional methods, Corado said she is working on opening a nail salon soon.

“Ms. Fabiana treated us as if we were her family, her kids,” Corado said. “She was not only in charge of educating us, she also provided us that motherly love that a lot of us in ESOL were missing.”

Helping students deal with trauma and standardized testing

Despite being beloved, Parker feels she isn’t doing enough to help her students. Any given day may include one-on-one lessons with a new student who has no English background or dividing her attention among as many as 16 students who need help refining their academic vocabulary. She is the only ESOL teacher at Thornburg Middle School, where 43 ELLs depend on her for physical and emotional help. And Parker said she must also be tactful in helping students who have escaped traumatic situations. Although most of her students are Latinx — 91,443 ELLs statewide are Latinx, according to VDOE — she has begun teaching more students from Afghanistan after the Taliban took over the country in 2021.

“Some of my Afghan students, they may speak their language — Farsi or northern Pashto or southern Pashto — but they cannot read or write in their language,” Parker said. “So when you don't have that first language, where you cannot read and write in the first language, it is much more difficult to learn English. Not impossible, but much more difficult.

“We have to start with the basics: letter sounds. I have to teach numbers; their number system is different; the letter system is different. We write from left to right; they write from right to left. So it is a much more delicate process and a much longer process, but it's successful. A lot of my students do quite well.”

Many Afghan families have resettled to Northern Virginia because of a refugee center that existed in Quantico, said Mariam Kakar, Virginia’s program manager for the nonprofit Women for Afghan Women. Kakar, who used to be a special needs teacher, hears concerns from parents whose children’s mental health is suffering.

“A lot of these young adults or these teenagers are going to end up suicidal, or depressed or maybe connect with the wrong people,” Kakar said. “I want them to become successful, and I think that they need more support emotionally because they went through trauma, too.

"They left their home behind. They left their schools, their friends, their clothes, their furniture, their everything. But they're not allowed to just be kids now here either, because they have so much to intake.”

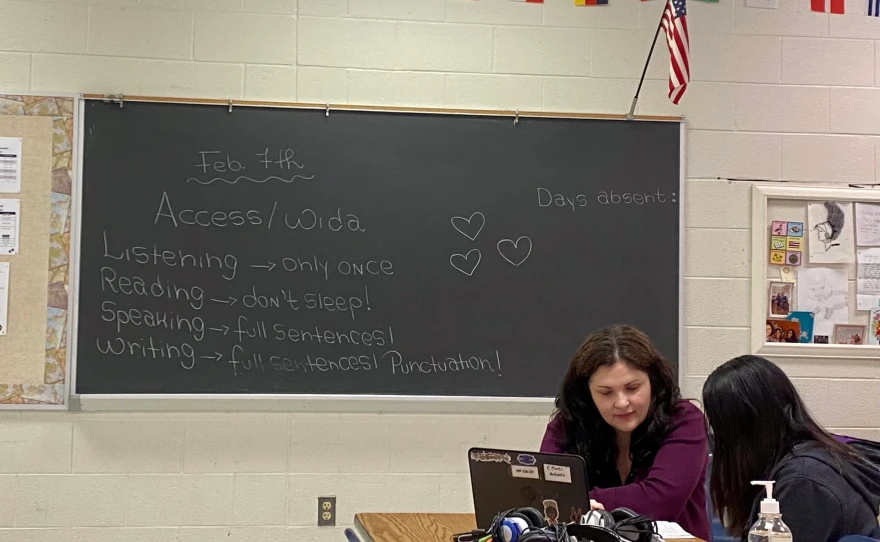

This time of the year, Parker has to help all her students prepare for the WIDA Consortium’s English proficiency assessment. The test consists of four sections graded on a 1–6 scale: listening, reading, speaking and writing. The test results determine which students will continue in the ESOL program, with an average of 4.4 indicating they are ready to exit. But even if the students no longer need daily help from Parker, she is federally required to monitor their progress and make sure other teachers continue to provide accommodations.

On top of that, ESOL teachers have to file paperwork for each student to track their progress, said Sharon Fitzgerald, an ESOL teacher at Osbourn High School in Manassas City. Fitzgerald has been an ESOL teacher for 11 years and worked alongside Parker at Culpeper’s Eastern View High School. Currently, she manages caseloads of more than 40 students in the 11th and 12th grades at Osbourn.

“That's also part of the reason why teachers don't necessarily want to teach ESOL students,” Fitzgerald said, “because there's extra work that has to be done, and there's no extra money for it.”

Reflecting wages

The grant incentives from SB 1118 would give ESOL teachers extra money for the extra work they are doing. Public school teachers who obtain endorsements to teach English as a second language for pre-K through 12th grade would get $5,000 the first year and an annual grant of $2,500 while the endorsement is active. This proposal also prioritizes smaller schools with poverty rates above 20%.

Manassas City likely would not see much of the funds from these proposals, according to Fitzgerald. The school division has seen a 21% increase of ELLs in the past five years, according to VDOE, with 579 currently enrolled at Osbourn High School. But looking at the statistics, Fitzgerald says counties like Culpeper and Spotsylvania are in dire need of the funding that Hashmi’s bills would provide.

“The population [of ELLs in Culpeper County] is just growing,” Fitzgerald said. “So, they are where Northern Virginia was 12, 15 years ago. They're behind. When Fabiana and I worked there, it was just exploding.”

As school divisions across the state struggle to find teachers for at least 3,573 unfilled positions, it will become even harder to find educators willing to pay for an ESOL teaching endorsement without guaranteeing greater earning potential, Fitzgerald said. This is why providing a monetary incentive for teachers is crucial.

The House Elementary and Secondary Education Subcommittee voted unanimously to kill Avoli’s bills on Jan. 25. Republican Del. Nick Freitas, who represents Culpeper, was one of three delegates who voted against the bills at a committee meeting on Jan. 23. Freitas was not available for an interview.

“How can you possibly oppose the development of an English language for English learners?” Avoli said. “It's a small pittance to make life easier for not only the kids, but for the parents.”

Though Hashmi’s bills received uncontested support in the Senate, they are likely to encounter opposition in the House of Delegates. Lawmakers now have less than a month to decide the future of English language education in Virginia.

The University of Richmond bureau of the Capital News Service is a program of Virginia Commonwealth University's Robertson School of Media and Culture. Students in the program provide state government coverage for a variety of media outlets in Virginia.

Disclosure: VPM News is pursuing litigation against the Virginia Department of Education over open records laws.