Two connected special exhibits at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts highlight the work of pioneering Black artists: Richmond native Benjamin Wigfall and New York–based Whitfield Lovell, whose immersive look at Jackson Ward is featured.

“Chimneys” by Benjamin Wigfall — an abstract, vivid rendering of smokestacks from the now-defunct Marshall Street Viaduct in Richmond — is at the front of the first exhibition.

“It is so local, and inspired,” said exhibition co-curator Sarah Eckhardt about the painting. “I love [Wigfall’s] philosophy that he believes in the nobility of the ordinary. And I think that work really captures that sentiment”

When the VMFA first bought this piece in 1951, it made Wigfall the youngest artist in the museum’s collection — at the age of 21. Now, the gallery is full of pieces that honor his life’s work — and the legacy he left behind.

Wigfall was a native of Richmond’s Church Hill neighborhood, who spent his life fostering community around art until his death in 2017.

Eckhardt said — although Wigfall was a pioneering and beloved artist — it was somewhat difficult to track down his individual works. Eckhardt and co-curator Drew Thompson worked with Wigfall’s family and estate to gain access to a vast archive of his artwork and documents.

“He was very humble, and he tended to put his energy into teaching and featuring other artists' work,” she said. “That archive really informed the way we approached the exhibition, because we were looking at how Benjamin Wigfall engaged community and how he wrote about it”

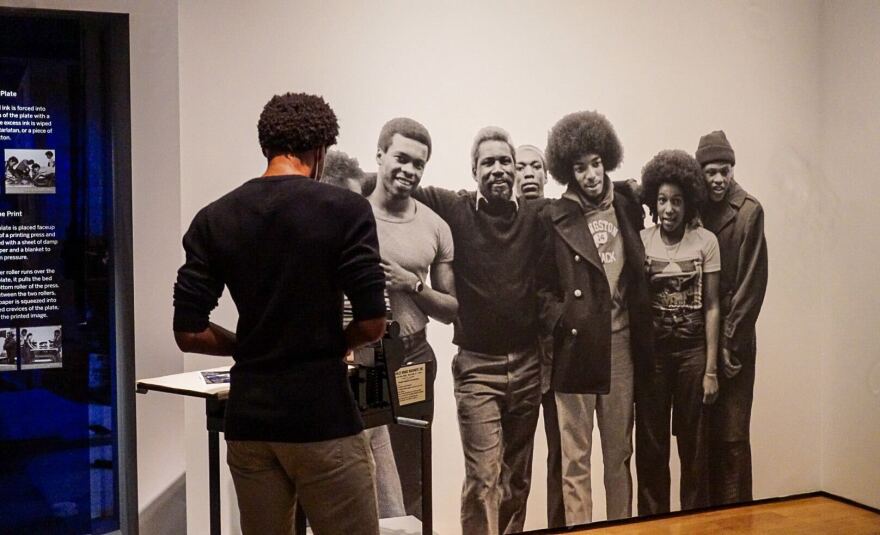

That community engagement is on full display in the middle section of the exhibit, which brings in artwork, writings and images from “Communications Village” — an art studio Wigfall founded in Kingston, New York. The “Village” functioned as a community space where young people could learn and share art.

Eckhardt shared what she views as one of the Communications Village’s primary philosophies.

“You don't have to leave your community to make art. You can find it around you,” she said. “And almost anything can be the subject of your art. You sometimes just have to change the way you're looking at it.”

Quotes from Wigfall’s former students can be found in a video screening — and on the walls of the exhibit.

“It was always dark, and then the lights came on. He was the light,” reads a message from Dina Washington and Theresa Thomas Washington.

A large portion of the Communications Village section is devoted to the art of printmaking. The Village hosted a number of printmaking courses, and Wigfall himself was a professor of printmaking at the State University of New York, New Paltz.

Eckhardt explained that the medium represents Communications Village’s spirit of collaboration.

“The process of printmaking really is open to the community, because multiple people can participate. An artist might make an image and etch the plate, but then other people be a part of making the print,” she says. “So there's a lot of images here, where you see a community coming together to actually realize the vision of an individual artist.”

The final room of the Wigfall exhibition serves as a realization of one of the artist’s lifelong goals.

In his writing, Wigfall expressed that he wanted to create an exhibition that highlighted the work of Outstanding Black artists, “to present another facet of truth through which America can view itself.”

Eckhardt and Thompson even used Wigfall’s written curatorial criteria to select major works from Communications Village — and bring his vision to life.

“It was really nice to not only show Benjamin Wigfall as an artist, but also as a curator,” said Eckhardt. “That was his artistic vision. He wanted to promote a vision for community.”

The end of the Wigfall exhibit leads into the beginning of “Passages” — a traveling installation focused on the work of Whitfield Lovell.

As a contemporary artist, Lovell uses multi medium, multisensory artwork to question collective understandings of American history.

Much of his work utilizes historical portraits of Black Americans from the 19th and 20th Centuries. After finding forgotten photographs in archives, thrift stores or on eBay, Lovell re-imagines the images by drawing them on salvaged materials — or by pairing them with found objects.

This unique approach to portraiture is seen in his “Cards” series, wherein Lovell connects his drawings of anonymous individuals to different antique playing cards — giving special attention and character to each person.

“He’s giving you something tangible to go along with the ethereal quality of these images of people who are no longer here and no longer living,” said curator Alexa Assam. “You bring new life to them by bringing them into your artwork or into a museum.”

In 2001, Lovell came to Richmond for a six-week residency and created “Visitation: The Richmond Project” — an immersive homage to the Jackson Ward community.

In his research, Lovell found a 1917 NAACP charter with the names and addresses of Jackson Ward residents from the time. A voice over the loudspeaker reads out those names on a loop.

Working with VCU Students, Lovell also found and collected local wood to create the five-part installation — which features multiple portraits, a sculpture and a period-accurate recreation of a 20th century parlor room.

“He really likes working with objects and items that have history to them. He’s taking these pieces of wood and not changing them for what they are,” Assam said. “If they still have paint on them, he uses them. If they still have wallpaper on them, or scuff marks or gunshot holes, he wants to bring forth that narrative.”

Although the exhibits are separate, Eckhardt and Assam’s observations revealed a commonality between them: the artists’ shared commitment to preserving Black American legacies — and highlighting the beauty of everyday life.

The exhibitions are available to view until Sept. 10.