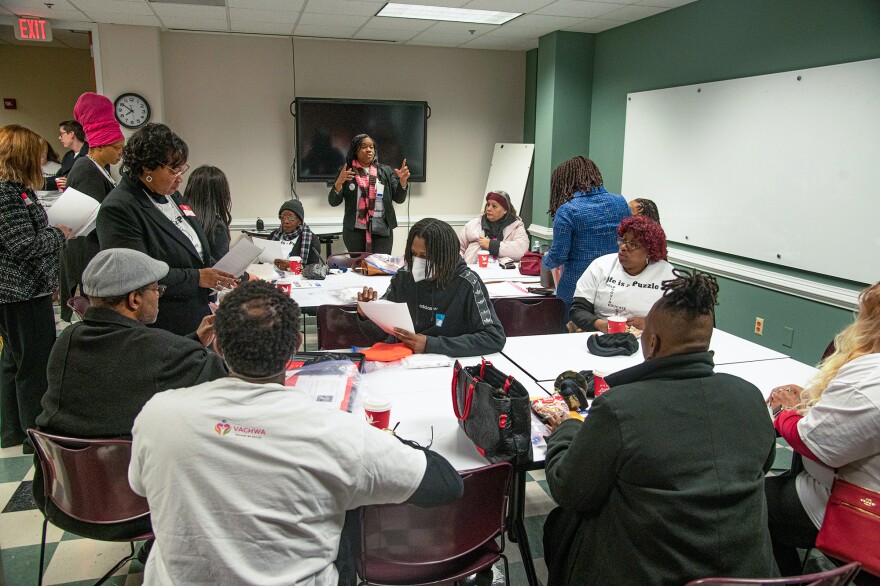

It was 9 a.m. and freezing Thursday when Shanteny Jackson was walking down Richmond’s East Broad Street toward the Virginia General Assembly Building with a team of Community Health Workers, policy analysts and allies.

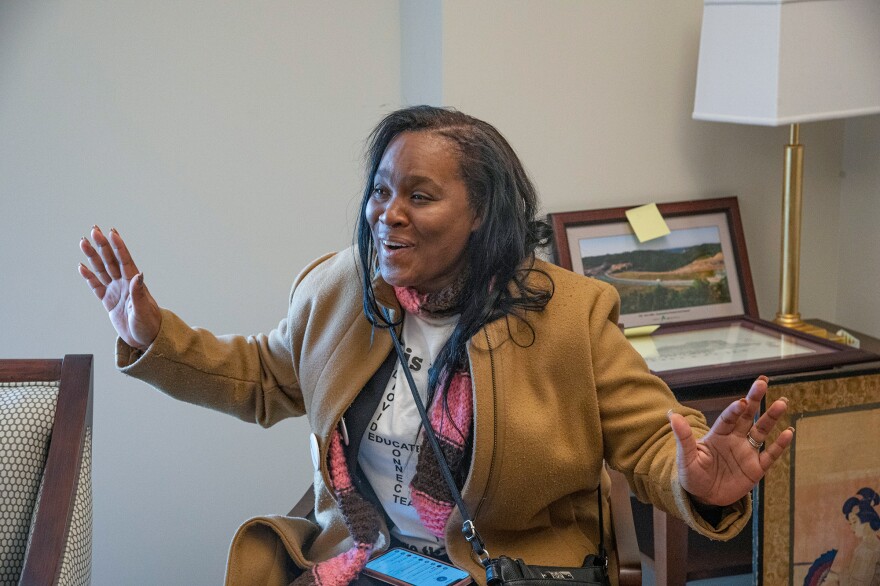

Jackson — who is executive director of the Virginia Community Health Worker Association — had been awake since 3 a.m. But the association’s Community Health Worker Awareness and Education Day was just starting.

“We have amazing people with us, we have partners who will help us get the message out,” she said while crossing 7th Street.

For Jackson and the CHWs, the aim of the event was to inform legislators about what they do and to raise awareness of a July 1 funding cliff that will see the Virginia Department of Health lose funding for about half of the CHWs employed at local health districts.

For allies working in policy, advocacy and other fields, the goal was to encourage legislators to vote for two proposed legislative fixes to the funding cliff.

CHWs are front-line public health workers. Many come from within the communities they serve and have personal experience with or connections to the health issues they’re addressing.

They’re often some of the only public health workers to have the trust of communities that have been ignored or mistreated by the U.S. public health establishment, such as Black Americans and immigrants who are not fluent in English.

CHWs have played essential roles in COVID-19 vaccination efforts, maternal and child health, substance use prevention and countless other public health initiatives around the commonwealth.

But without legislative action, the July 1 funding cliff will hamstring many of these efforts.

The funding cliff and efforts to address it

“Community health workers, regardless of where they are employed, are important to communities,” Jackson said as she reached the door of the new General Assembly Building. “And so we want to be consistent in the service quality that we provide — not just for us, but for the organizations, for the programs and wellness of our communities.”

The group of about 25 people split into seven groups, mostly made up of two CHWs, a policy advocate and another ally. Over the course of the day, those groups met with about 30 Virginia state legislators.

As VPM News/WMRA previously reported, over half of 112 known positions at health districts will lose funding by July 1 because of the funding cliff. And more than 25 additional workers will also lose their jobs in the year after that.

One internal VDH document VPM News/WMRA obtained reported 96% of Virginia health districts “strongly agree that loss of funding for CHWs will negatively impact one or more health department programs or services in their health district.” Twenty-five of Virginia’s 35 local health districts participated in that survey.

CHW group seven was made up of Jackson, Tameca Day and Ben Barber. Day is a CHW in Richmond and Barber is the policy director for Virginia Health Catalyst, a nonprofit oral health policy and advocacy group.

The first conversation for the group was with Southwest Virginia Del. Will Morefield (R–Tazewell) Thursday morning. After Jackson and Day talked about the work they do, Barber explained the funding cliff to Morefield.

“We have about 100 community health workers who are already funded, they're at local departments of health across Virginia — including a lot in Southwest Virginia,” he said. “They were funded through federal COVID relief dollars. That money is going away starting July 1.”

As Morefield nodded, Barber continued, “So we have these 100 community health workers, they're doing all the great things that Tameca and Shanteny are doing in their communities: It's gonna go away unless we can find the money to keep those positions funded.”

Then he requested Morefield’s support for a bill and a budget amendment.

What are legislators proposing?

Together, the two fixes stand to sustainably fund health districts’ CHW positions and allow other institutions like hospitals and schools to expand the care they provide to populations they have long neglected.

The CHW budget amendments are being led by state Sen. Lashrecse Aird (D–Petersburg) and Del. Mark Sickles (D–Fairfax County). If passed, VDH would receive an additional $3 million each year between July 1, 2024, and June 30, 2026, specifically to fund CHW jobs.

The amendments prioritize funding CHWs in health districts experiencing high maternal mortality rates.

The average pay for a CHW employed at one of Virginia’s local health districts was $50,141 as of July 2023, according to documents VPM News/WMRA obtained through public records requests.

Gov. Glenn Youngkin’s roughly $175 billion two-year operating budget includes a record-high $2.2 billion in funding for the Department of Health. The $6 million for CHWs would represent about one-third of 1% percent of VDH’s proposed budget.

The bills, HB 594/SB 615, are being led by Sickles and state Sen. Todd Pillion (R–Washington County).

If passed, they would direct the Department of Medical Assistance Services to start a “work group of stakeholders to design the certified community health worker services benefit and to seek federal approval through a state plan amendment to implement the benefit.”

In simpler terms, that means they would start the process of allowing institutions that employ Certified CHWs in Virginia to be reimbursed by Medicaid for some of the care the CCHWs provide to people enrolled in Medicaid.

(Medicaid is free or low-cost government-provided insurance that covers low-income people and people with some disabilities. In Virginia, the program is administered by the Department of Medical Assistance Services.)

The bills would apply to CCHWs employed by health districts, hospitals, schools and other institutions. There are about 1,300 CHWs in Virginia, according to federal Bureau of Labor Statistics data from 2022. Jackson said about 300 of them have completed the certification process to become CCHWs so far.

Medicaid reimbursement for CCHWs’ work is an important step to sustainable funding, according to Virginia Health Catalyst CEO Sarah Bedard Holland.

Right now, a lot of the care doctors and other medical practitioners provide for Medicaid enrollees is paid for by Medicaid. But similarly important and complementary services like blood pressure monitoring are not reimbursable by the same program when a CCHW does them.

Bedard Holland said the bills would start the process of changing that, which would have ripples across the commonwealth’s health system: “It makes it financially possible for [a medical] practice to hire a community health worker because they can pay for the community health worker.”

More than 20 states reimburse at least some CHW services, according to a 2021 report from the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. In recent years, Virginia has approved similar Medicaid reimbursement policies for state-certified doulas and certified peer-recovery workers.

Will small victories add up to a large one?

After hearing Jackson, Barber and Day’s case for sustainable CHW funding, Morefield highlighted his work finding bipartisan solutions to rural issues like population loss and talked about the importance of preventive care in his district.

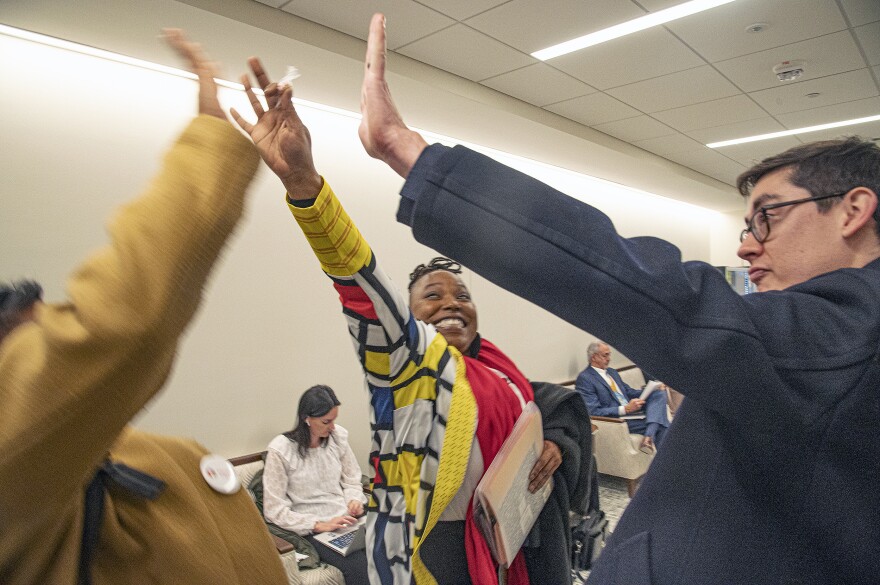

Then the Republican told the group where he stood on the bill and budget amendment: “Whatever we can do at the state level to provide assistance and a long-term revenue stream, I'm certainly supportive,” he said. “I see tremendous value in what you all are doing.”

After two rounds of thank yous and a group photo, the trio left Morefield’s office, rounded the corner into the hallway and high-fived. Half an hour into the CHW Awareness and Education Day, and they had scored their first victory.

Kathryn Haines is health equity manager at the Virginia Interfaith Center for Public Policy and has been closely involved with getting the legislative fixes to the General Assembly. Sitting in the General Assembly Building’s cafeteria, she told VPM News/WMRA this type of work is all but necessary to get a bill passed.

“Because both in a short legislative session and a long legislative session — we're in a long legislative session this year — you have about 2,000 bills,” she said. “That's 2,000 bills in two months.”

Haines said, generally, less than half of those will be passed, let alone signed into law. With legislators getting as many as 500 emails a day, “You need to be in person talking to your legislator.”

And the stakes are high for the bill and budget amendment. In addition to the funding cliff that more than 60 VDH CHWs face, Haines said many of the CHWs who do stay will have their work disrupted by job changes.

“A department might have to go to them and say, ‘I know you're a community health worker and you have been working on substance abuse because that is the No. 1 problem in our area. But you can't do that anymore because the grant is over,’” she said. “The grant basically drives the work, instead of the community need.”

Bedard Holland echoed the issues of grant-based funding and emphasized the benefits of moving to a Medicaid reimbursement model for supporting CHWs.

“We cannot philanthropy our way out of this problem,” she said. “Offering Medicaid reimbursement is a way to help ensure that community health workers can stay a part of the health care workforce for a long time to come.”

While many of the federal grants that have funded the CHW jobs run out on June 30, the proposed budget amendment would fund the positions from July 1 for the next two fiscal years. (Virginia’s fiscal year runs from July 1 through June 30 each year.)

And on the Medicaid reimbursement end, if HB 594/SB 615 becomes law, reimbursement for some CCHW services could happen as early as 2025 — though it would likely take longer.

If both fixes make it through the General Assembly and Youngkin signs them into law, the funding cliff would be eliminated and the commonwealth would be on the way to what advocates said is sustainable, long-term funding for CHWs.

But that’s still a big if.

“Everyone always asks me what's going to happen as if I had a crystal ball, and I can never answer that question,” Haines said. “What I can say, having done work similar to this for about 20 years, is that we have done all the things that we need to do in order for the bill to pass.”

Whatever happens, the situation for CHWs has catalyzed broad support. In addition to policy institutions like the Virginia Interfaith Center for Public Policy, Virginia Health Catalyst and the Institute for Public Health Innovation, Virginia’s large and influential hospital trade association — the Virginia Hospital & Healthcare Association — has thrown its support behind the legislation.

And that broad support provides advocates and CHWs with hope.

“I don't remember when I've heard so many people talking about public health,” Haines said. “It's exciting to see the engagement and hope [among CHWs], ‘I might be able to continue this excellent work,’ because it's all eyes on community health workers.”