Virginia lost about 9,500 acres of forested land to development from 2014-18, according to data from the Chesapeake Bay Program and Chesapeake Conservancy.

Some localities have the option to slow deforestation by adopting tree replacement and conservation requirements for new developments. And new legislation in the General Assembly could empower all counties, cities and towns in the commonwealth that way.

Trees have a wide range of benefits in urban and suburban environments. They provide shade that moderates urban heat islands, reduce the effects of flash flooding, filter pollutants from runoff and support biodiversity.

As heat waves and torrential downpours become more intense and more common, environmentalists say trees represent one of the most cost-effective ways to cope with climate change.

Conservation and replacement

Localities in the Chesapeake Bay watershed and densely populated cities can implement tree replacement requirements. Under those ordinances, developers have to ensure that 10%-20% of their property is covered by tree canopy 20 years after construction, depending on the type of development.

Northern Virginia localities in planning district 8 that don’t meet national air quality standards for ozone can also require the conservation of trees during development, ensuring that a percentage of mature trees are left intact. Those localities can require up to 30% canopy on some residential sites after construction.

Environmentalists say conservation is preferable to replacement: Mature trees do more to provide shade, slow runoff and improve air quality.

“It takes more than 10 years to achieve the same result as with brand-new planted trees,” said Ann Jurczyk, Virginia director of advocacy and outreach with the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, a conservation organization. CBF worked with legislators and other stakeholders on the bill.

The existing law also allows localities to set up tree canopy banks and funds. If a developer is unable to meet the minimum canopy requirements due to engineering or environmental constraints, they can contribute to a bank that plants trees on other pieces of land or pay out equivalent cash value (as determined by the locality) to a fund for tree giveaways, maintenance and other programs.

Going statewide

Del. Betsy Carr (D–Richmond) is carrying a bill that would allow any locality in Virginia to adopt conservation requirements, not just the ones in planning district 8. Del. Karen Keys-Gamarra (D–Fairfax) carried a similar bill, which was incorporated into Carr’s.

The measure — if passed by the General Assembly, signed by Gov. Glenn Youngkin and then adopted by City Council — could help Richmond meet its master plan goal of 60% tree canopy by 2037. 2010 data referenced by the city shows Richmond has 42% tree canopy — the Bay Program’s 2018 data puts it at 32%. According to Richmond Urban Forester Michael Webb, the city can’t meet its goal without more trees on private land.

“If we planted every single vacant area along city right of way, we still would not come to that 60%,” Webb said.

He said extending the option to set a conservation requirement would be “monumental” for cities looking to expand their tree canopies.

City Councilor Katherine Jordan sent a letter in support of the bill last week.

Another bill sponsored by state Sen. Suhas Subramanyam (D–Loudoun) would allow localities to spend cash deposited into a tree canopy fund on private property. Current law limits that cash to public lands.

“In any municipality, only approximately 20% of land is owned by the municipality,” said Jurczyk with the CBF. “If we want really to increase and bump up our tree canopy, we’ve gotta make that available to homeowners and businesses and other people who have that greenspace that’s available for planting.”

Of the seven localities that can currently implement the conservation ordinance, only Fairfax and Arlington counties have done so. Del. Keith Hodges (R–Middlesex) questioned why; Carr reiterated that existing state law doesn’t impose any requirements on localities in planning district 8.

According to Jurczyk, if an eligible locality chooses to adopt the replacement or conservation requirements, it must adopt the whole package.

“It might be too prescriptive for them. I think that they may want something that's more flexible,” she said. “But our goal this year was to make sure that both replacement language and conservation language was available statewide.”

At a committee hearing on Carr’s bill, Randy Grumbine of the Virginia Manufactured and Modular Housing Association said most construction their members do would qualify for the highest conservation requirement of 30%.

“When you have to clear a large area to provide a septic field, it’s difficult to get the canopy coverage that this bill would require,” he said.

Grumbine acknowledged there is an appeals process included in the bill, but he said that would be costly and time-consuming for developers. VMMHA opposed the measure.

Sprawl and shade

Although Richmond has lost some tree canopy — 80 acres, about 0.5% of the total acreage — most of the acres lost in Central Virginia from 2014-18 are attributable to counties. As the urban sprawl of Richmond and other cities turns more of their surroundings into low-density, car-dependent suburbs, forests are threatened by new roads, homes, businesses and parking lots.

Henrico County saw a net loss of 1,037 acres of tree cover to development. Chesterfield County lost 2,571 acres. That’s about a 1.4% decline in canopy for both counties. Neither county added more than 215 acres of tree cover in that time.

Fairfax County and Arlington County have both adopted tree ordinances under the conservation law. From 2014-18, Fairfax had a net loss of 737 acres — and Arlington saw a net gain of 1 acre.

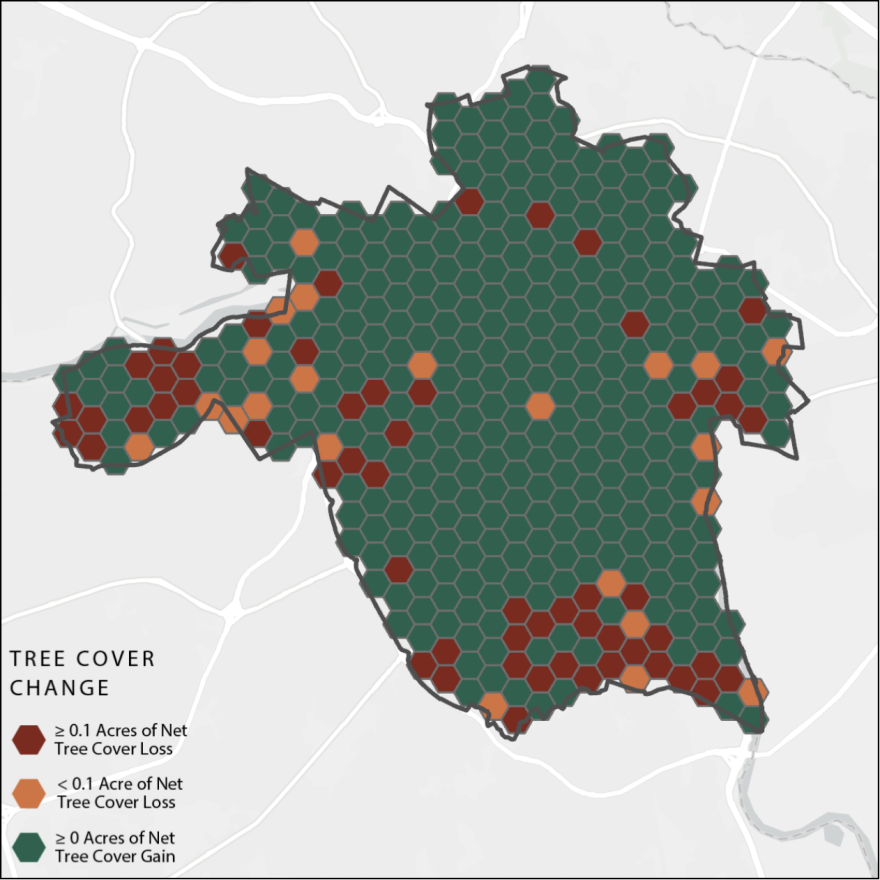

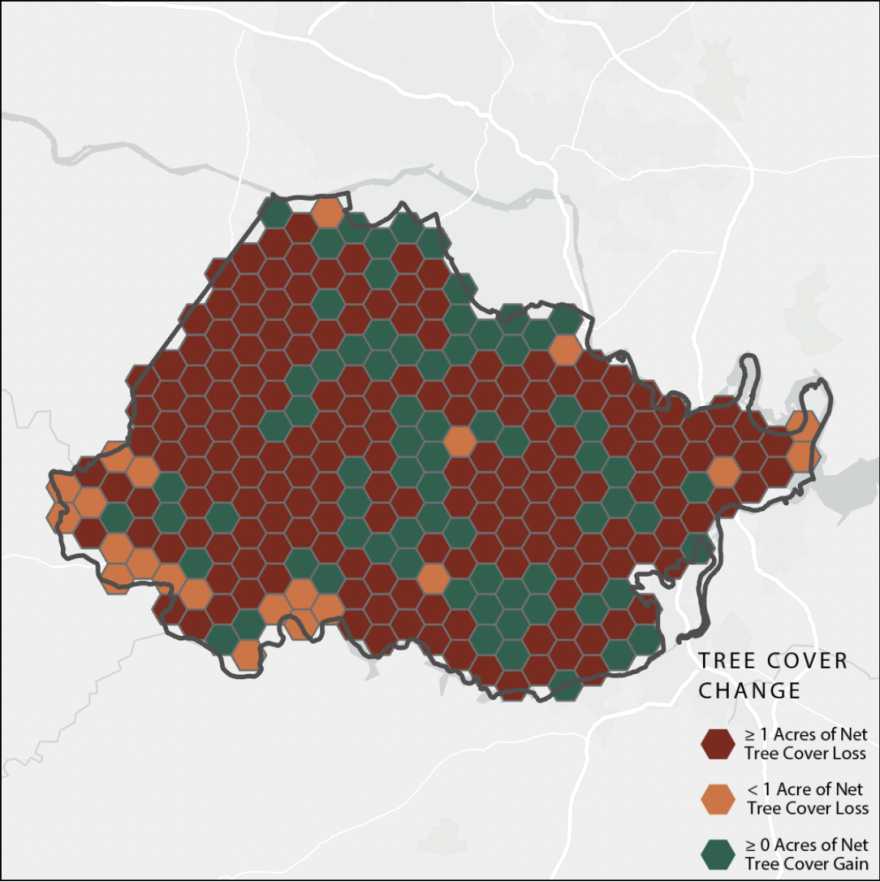

Other differences emerge when viewing maps of the localities with tree cover change superimposed on them.

Richmond’s tree canopy loss was concentrated in the city’s western tip and along its southern border, but most of the city’s land either saw no change or an increase in its overall cover.

The decline is more uniform in counties: Chesterfield and Henrico both had less shade across most of their land by the end of the sample period.

Canopy studies

Subramanyam submitted a budget amendment that would require the Virginia Department of Transportation to “conduct a study of tree canopy loss due to road construction,” using the data gathered by the Chesapeake Bay Program. The regional partnership expects updated data on tree canopy for the years 2018-22 to be available by September 2024.

Lawmakers are also considering a bill from Del. Patrick Hope (D–Arlington) that would require the state Department of Forestry to develop a Forest Conservation Plan with a stakeholder group. The plan would include the current status of Virginia forests and tree canopies, select priority forests for conservation, identify funding mechanisms and more.

Hope’s bill received unanimous support in the House Agriculture, Chesapeake and Natural Resources Committee and is waiting to be heard in House Appropriations. A similar measure in the Senate, sponsored by state Sen. Dave Marsden (D–Fairfax), was unanimously approved by a committee Tuesday.

All bills in the General Assembly must be heard by early next week, or they’ll be left behind in crossover.