To see more coverage of the Virginia School for the Deaf and the Blind, watch Thursday’s episode of VPM News Focal Pointon the PBS App or VPM PBS.

When Carina Groll first started living on her own, she learned some of the same lessons most people do: It can be hard to budget your time, figuring out dinner each night is a chore and the microwave is a particularly useful appliance.

On an average weekday, she might take the bus to work, go to classes, then pick up some groceries and head back to her apartment.

Her life is similar to most college students, except she’s a 17-year-old high schooler.

That independence isn’t because she’s on her own. Instead, it’s because she’s a student at the Virginia School for the Deaf and the Blind who participates in the school’s innovative programs.

The Shenandoah Valley institution serves deaf, deafblind and blind students like Groll, who is blind.

There are currently 65 students enrolled ranging in age from 2 to 22 years old. The majority of older students live on campus during the week before returning to their homes around the commonwealth on weekends. Because the school is state-run, there is no cost to students or their families for any program or service, including transportation.

Superintendent Pat Trice said VSDB’s mission is to build independence among students for life after they graduate.

“We teach the academics, but we also teach life,” she said. “We want them to be able to be independent, and it's amazing when they realize what they can do.”

The school’s mission is a battle against persistent stereotypes that can prevent people with disabilities from getting and holding jobs they’re capable of doing. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 37% of working-age people with a disability were employed in 2023 compared to 75% of people without a disability. In the U.S., 13% of people have a disability.

(While VPM News/WMRA could not find exactly comparable and recent data specifically for deaf, blind and deafblind Americans, in 2017 a little more than half of working-age deaf people, a little less than 40% of blind people and just over one-third of deafblind people were employed.)

This and other factors combine and lead to a poverty rate that’s twice as high for people with disabilities, according to the National Disability Institute’s analysis of American Community Survey data. The data also shows rates are highest for Black and Latino people with a disability.

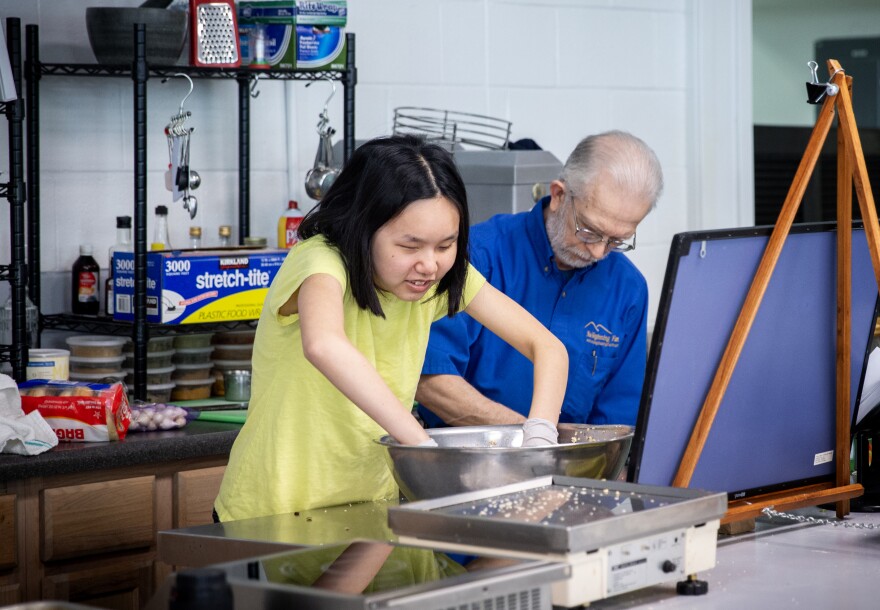

The school has developed a range of programs to help students live with confidence, independence and autonomy. Groll works at the Nu-Beginning Farm Store in Staunton. She spoke to VPM News/WMRA while making the store’s homemade vegan and gluten-free granola.

“I love doing food preparation,” she said. “I think the best part about doing the granola is mixing, for sure, because it's so therapeutic, especially with your hands.”

Her unpaid work-study job is part of the school’s workforce training program, Achieve. In addition to food preparation tasks, Groll has helped with varying IT issues, like fixing the iPad that Nu-Beginning uses to accept card payments. While she hopes to attend James Madison University after VSDB to study information technology, Groll said the work experience is helpful.

“I believe this is going to help a lot in my life,” she said. “Because I am learning this experience early on … while gaining some good work experience that can be good for the resume and for employers.”

Sharon Ernest is a transition specialist for VSDB and runs the work-based learning program that offers unpaid internships in businesses around Staunton. She’s been with the school for nearly 20 years and said the program is essential, because it gives students real-world work experience while also building self-worth.

“Our students, they're proud of themselves when they can do something,” she said. “In the world of work, anyone feels value from that. We want people with disabilities to feel the same way: to feel valued, worthy — that their contributions to society matter.”

Nu-Beginning owner John Matheny has worked with eight VSDB students, including Groll, and said the value of their work is real and equal to that of a seeing or hearing peer.

“If I have a 16-year-old kid that walks in off the street and wants an application, this is his first job, OK? Or [if] I have a kid that comes down from VSDB and this is their first job, where's the difference?” he asked. “Both of them need to be trained.”

To Matheny, the idea that people with disabilities have less to contribute is “grossly incorrect.” Instead, he said the students are a resource.

“Yeah, they're getting something out of it,” he said “But so are we.”

The work-study program isn’t the only way students are preparing for the workforce after VSDB. Ernest said students have other options, including an array of on-campus jobs and the ability to take classes at Blue Ridge Community College or Valley Career & Technical Center.

“It just depends what the students need,” she said. “We try to make it fit, so that they can get the most out of their educational experience.”

And while work is one component of life after school, VSDB also helps students prepare for living on their own.

The school’s flagship program is its Independent Living Apartments. The program started about eight years ago, after two years of fundraising by the VSDB Foundation. Eligibility only comes after a curriculum designed to prepare students for living on their own: They’re taught how to check leases, inspect apartments, put in work orders, do laundry, use fire extinguishers and cook healthy meals.

For nine weeks, students in the ILA are assigned apartments of their own. They’re divided into groups, like blind boys or deaf girls, and during that time, each does almost everything themselves.

Trice said the biggest adjustment is shopping for themselves every week. Students take the city bus or a school van to the store to get groceries. It’s an experience rich with life lessons, and VSDB gives students a low-stakes space to learn them.

One common budgeting mistake the students make is spending too much on junk food they can’t have at home with their families.

“They realize, ‘I don't have anything to eat for dinner,’” she said. “We give them a little bit of leeway in the beginning, because we're not going to let them go hungry. But it is a really good lesson.”

The appliances in the apartments are accessible to students, with specifically accessible features like stoves with knobs that allow blind students to tell if they’re turned on or not. But the catch is students are given a fixed amount of play money to purchase items at the school store. They range from accessible measuring cups to a student favorite: the microwave.

Trice said the ILA experience simultaneously prepares students and teaches them self-reliance: “There is nobody telling them to go to bed, there is nobody telling them to wake up. If they're late for school, they get docked money, because they now have missed clocking in — that is their job.”

The goal, according to Trice, is to help students reach their highest level of independence.

“We want them to fulfill their potential, we don't put a cap or any low expectations on what they're able to do,” she said. “We push them and provide them with services, and teach them so that they can perform at the highest potential level that they have.”

While at school, Groll also fills her free time listening to audiobooks; playing piano, viola, guitar and bass; gaming; playing on VSDB’s goalball team and exploring computer software — especially accessibility technologies. The 11th grader said she is proud to have learned these skills, and that she cherishes the school’s learning environment.

“Self-advocacy was — is — a big challenge for me because I'm often nervous to be like, ‘Oh, hey, I need this.’ Or, ‘Hey, I need that,’” she said. “And what I often do to overcome it is I just give myself some positive self-talk and then I just straight-up go and do it.”