The 70th anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court's Brown v. Board of Education decision that found racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional is Friday, May 17.

One of the court cases that led to that decision began in Virginia, with calls for newer and better school facilities for Black students. This VPM News series examines the issue of school conditions — then and now — to unpack why so many Virginia schools are in disrepair, especially in districts like Richmond Public Schools, which remains largely segregated.

Part 2 looks at the history of Prince Edward County Public Schools, where the fight for equal schools in Virginia began.

A small group of Robert Russa Moton High School students in Farmville began gathering in secret months before an April 23, 1951, walkout to protest the unequal conditions of school facilities for Black students.

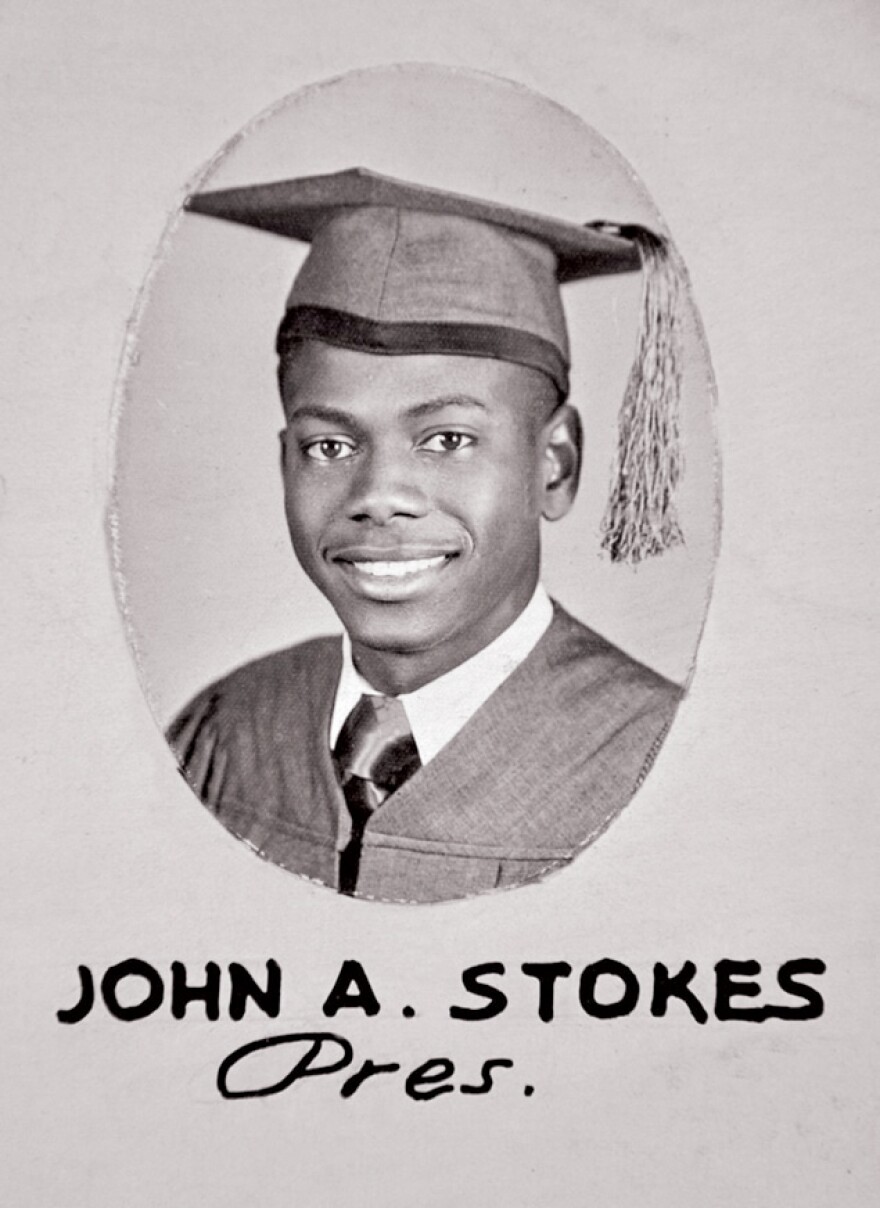

“It was the same type of secrecy that was developed during the Manhattan Project,” said John Stokes, one of the walkout’s organizers. “We had to trust everyone so we could pull this thing off.”

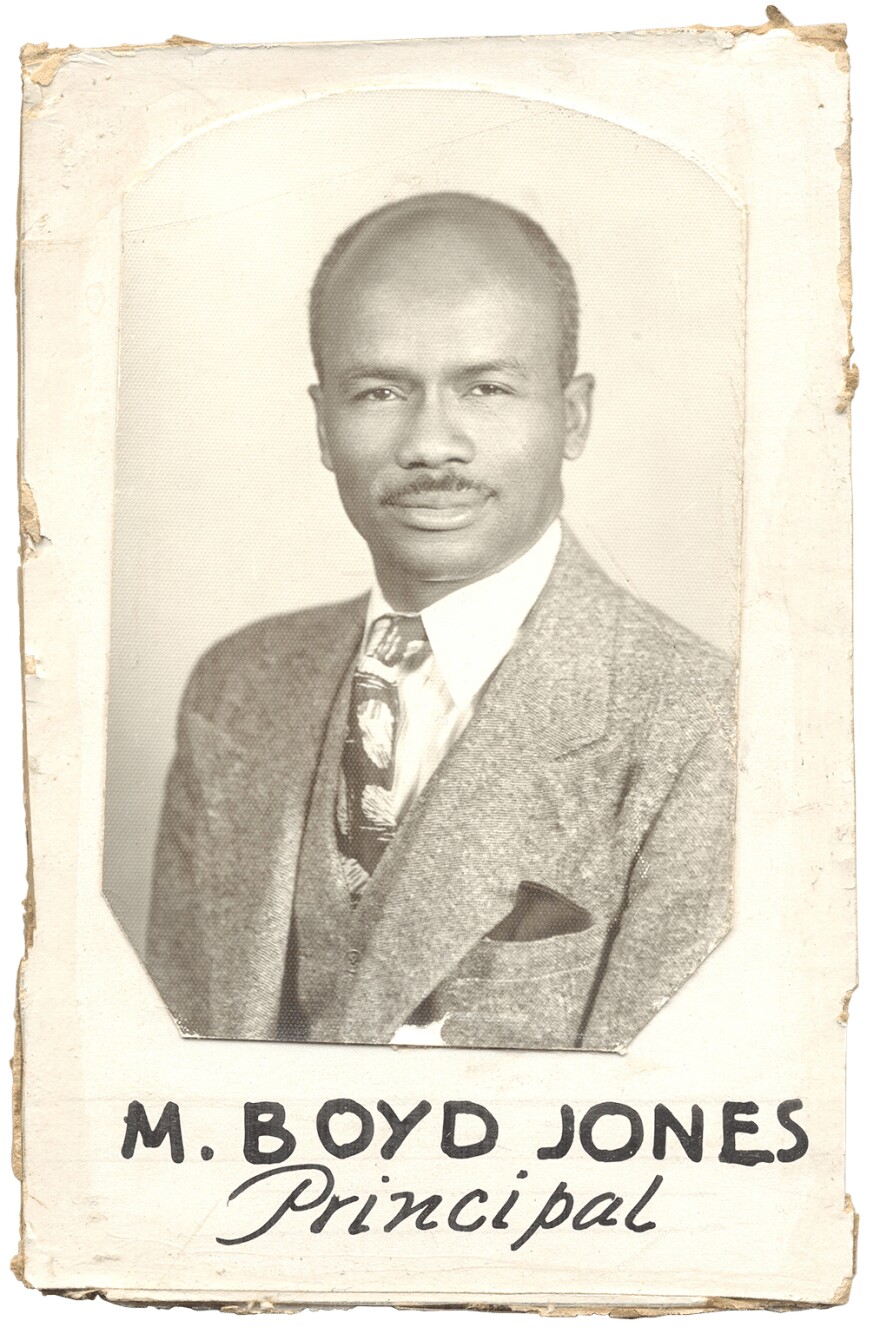

Students decided to report a fake disturbance downtown, luring Moton's principal Boyd Jones away from the school on the day of the protest.

“Mr. Jones did not want any of us to become involved with anything that wasn’t right in the neighborhood,” Stokes said. “So, at the time, he leaves. He goes down to find out who the troublemakers were.”

By the time Jones got back, the strike was in full force. About 400 students gathered in the auditorium to hear a speech from 16-year-old student Barbara Johns before walking out of the school in protest.

White students in the district enjoyed indoor plumbing and attended schools made of brick, while Black students used outhouses and some took classes in tar-paper shacks outside Moton high school, which were added to deal with overcrowding.

One Moton student recalled using an umbrella on rainy days, so ink wouldn’t run all over her paper.

“They had put up tar-paper shacks that were not fit for animals to inhabit. It leaked in there,” Stokes said. “They had no real siding. So, we knew we were being programmed for failure.”

But it wasn’t just the facilities that were unequal: so were curriculum materials and other resources. Stokes said he and his twin sister couldn’t go to school until they were about 8 years old because the division didn’t provide buses for Black students at the time, and they lived too far away to walk.

“The strike was on for two weeks … two whole weeks,” Stokes said.

After the 1951 walkout, Stokes said the school principal pleaded with them to end the strike, so he wouldn’t lose his job. But the students remained steadfast in their resolve. They gained the support of the Rev. L. Francis Griffin, who was in charge of the local NAACP chapter.

Griffin connected the students to NAACP lawyers, who eventually represented them in Davis v. Prince Edward County School Board. It became part of the Brown v. Board of Education lawsuit before the U.S. Supreme Court a few years later — with the majority of plaintiffs coming from the Davis case.

“We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place,” wrote Chief Justice Earl Warren in the unanimous 1954 Supreme Court decision. “Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

In 1953, a new high school was built for Moton students — but it was unoccupied for a year until the Brown decision could be decided.

“The problem was that if these students — the plaintiffs in Davis — accepted that new school building, they would have had to drop the lawsuit. And so, they turned it down,” said Cainan Townsend, executive director of the Robert Russa Moton Museum — which tells the story of the 1951 Farmville walkout and subsequent school closings.

The district’s schools remained segregated for another decade as Prince Edward County became notorious for closing its public schools rather than integrate them. The county’s schools remained closed for five years, from 1959 to 1964. During that time, white families received state-financed tuition grants to attend a private, whites-only segregation academy.

Some of the district’s schools, with a majority Black student population, are again in a state of disrepair today. State records show it’s been nearly 20 years since schools there have received significant renovations.

“The high school out of the three [schools] is not nearly the worst,” Townsend said. “Really, the elementary school has been in some rough shape for a while.”

The district’s superintendent declined a VPM News interview request.

Townsend's a lifelong Prince Edward County resident. His father, at the age of six, was locked out of school during the county’s school closures. Townsend said that meant his father worked instead of going to school for five years.

“He picked tobacco,” Townsend said. “He worked pretty much that entire time, because if they weren't at school, they were going to be working.”

His great-grandfather, as well as two of his great-aunts, were also plaintiffs in the Davis case that eventually was rolled into Brown v. Board.

When Townsend served as the Moton museum’s director of education, he regularly took school groups on tours of the museum. Once, he said, some local elementary students compared the conditions of their school to those tar-paper shacks.

“I’m talking about tar-paper shacks. And I’m like, ‘Yeah, when it rained, it poured inside the classroom. So, these kids would have to have umbrellas over their heads to try to keep the papers from getting wet,’” Townsend said. “And the kids are like, ‘Yeah, our classroom looks really bad, kind of like those shacks.”

There’ve been so many leaks at Prince Edward County Elementary School, they developed a “contraption” to funnel all the water into one spot.

In a March 2022 interview, Townsend drew a parallel to the underfunding of the county’s schools when they reopened in 1964 — after they were closed for five years — with present day underfunding of the public schools. Sometimes, county investments have come with strings attached, and some residents haven't wanted to invest in the schools either.

“The county doesn’t want to put more money into schools. Why? Because the test scores are bad. So, please tell me how not spending money to fix the environment is going to improve test scores. Now, you’re going to disadvantage them academically and physically? That’s what I’m hearing,” Townsend said in 2022. “Those are the kind of things where I'm just like, ‘You see how this is the same, right? It's different, but the same.”

The county now has plans to renovate the school, though they’re still working out how to pay for it. They’ve received a state grant and are planning to apply for a loan to help finance the work.

Townsend said in his most recent interview with VPM News that he’s pleased with the county's plans to renovate the elementary school.

"Everything's getting renovated, and then the worst parts are getting knocked down,” Townsend said. “But it's got a good strong foundation, a good skeleton."

The county’s elementary school principal and the county administrator did not respond to VPM News interview requests about school conditions and renovation plans.

History has continued to repeat itself, locally and nationally. Across the country, public schools are still segregated with the white student population dropping from 74% in 1988 to less than 50% three decades later. Meanwhile, Black students' representation at public schools has remained steady and the Hispanic student population has more than doubled.

Mary Filardo, executive director for the 21st Century School Fund, said the white flight that followed Brown v. Board — which continues today — has not only led to a decline in student enrollment in majority Black school districts, but also a decline in funding for new schools. This has impacted urban and rural districts like Richmond and Prince Edward County more dramatically.

“We’re still obviously dealing with the legacy of what has been kind of the privileged wanting to maintain their privileges and not really thinking about what that means as a country,” Filardo said. “So, we get greater disparity, rather than less.”

Filardo said numerous lawsuits over inequitable education spending across the country in recent years have drawn inspiration from Brown v. Board.

And despite Virginia’s connection to the case, the state has spent less on school construction during the past decade compared to many other states. While some states pay for about half the cost of new schools, Virginia has footed the bill for about 10% in recent years, leaving localities to figure out how to pay the millions of dollars needed to build new facilities.

On top of that, Gov. Glenn Youngkin recently vetoed legislation that would’ve allowed Virginia localities to seek voter approval to raise local sales taxes for new school construction. He said the state is already spending enough on education and he doesn’t want to raise taxes.

Prince Edward County has been seeking this authority on its own for the past few years, but has been denied by the state.

Townsend, who’s also a county school board member and parent of an elementary schooler in the district, testified before the Virginia General Assembly this year in support of the proposed legislation.

“I could not help but think of the sad irony that in 2024, I am still advocating for equity in Prince Edward Schools just as my family and many others did over 70 years ago in the 1950s and 1960s,”he wrote.

Part 1 looks at the current state of Richmond Public Schools and the consequences of its aging facilities.

Part 3 looks at potential solutions to ensure equal access to adequate school facilities.